Welcome to meryenda minutes, our audio companion illuminating Filipino chefs, doers, farmers, writers, scholars, artists plus more with insight into their food (and/or beverage) stories. Through this interview series, we aim to better bridge conversations spanning the homeland and the diaspora. We hope this contributes to a flourishing of a much more interconnected community and enrichment of Philippine culture + cuisine.

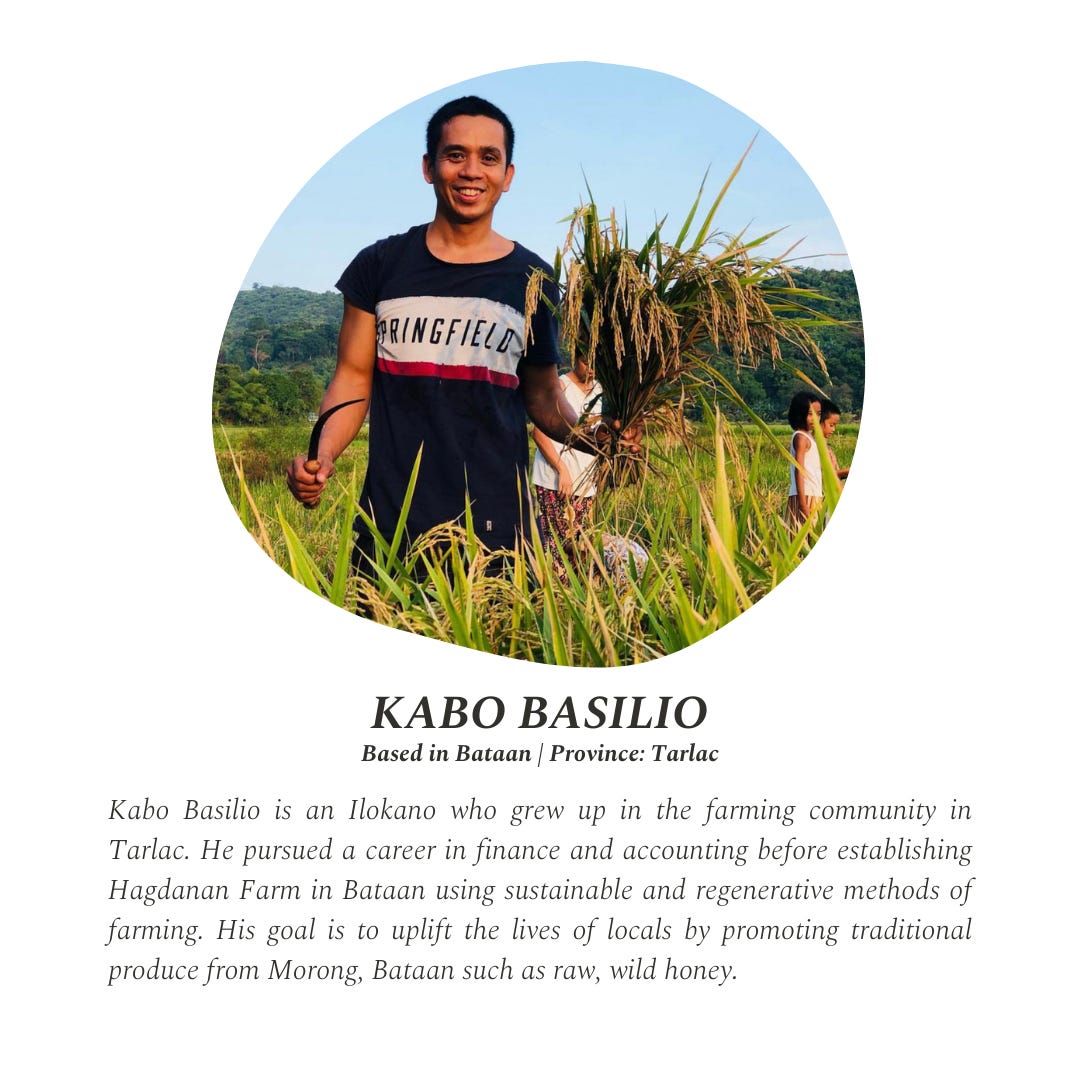

Kabo Basilio is an Ilokano who grew up in the farming community in Tarlac. He pursued a career in finance and accounting before establishing Hagdanan Farm in Bataan, central Luzon using sustainable and regenerative methods of farming. His goal is to uplift the lives of locals by promoting traditional produce from Morong, Bataan such as raw, wild honey.

After this episode, you might not think of honey in the same way again. I also invite you to this question: How does learning about our local honeybees open the door to the generosity of our forests? Maybe we can again find significance in the season of the mango trees, the Narra and Tanguile trees. Spring is not just a marker of a transition of seasons, but a time we share in nature’s abundance.

Note on honey: Wild honey is honey harvested from hives found in the natural environment whereas farmed honey is produced by domesticated bees under the care of a beekeeper typically at an apiary (from Latin word “apis” meaning “bee”). Raw honey may both be wild or farmed and refers to honey that skips the process of pasteurization (but may undergo light filtration) leaving enzymes, yeast, nutrients and aromas intact.

Commercialized honey is an entirely different discussion on its own.

*UPDATED June 1, 2023*

One of our readers shared a research paper stating that the Philippine giant honey bee, previously Apis dorsata breviligula, is now classified as its own species: Apis breviligula.

Jess: I really wanted to give this space to you. I wanted to hear about the honey. Maybe you could tell us a little bit about yourself and how you connected with with Denison (of Den and Jean’s Natural Farm in Batangas).

Kabo: Yeah, actually, I'm an auditor by profession, so accountant, auditor. I worked with big firms before: Deloitte, Ernst & Young, and also PwC. Now [my wife and I] moved to the private sector and afterwards actually we worked in Luxembourg in Europe for 12 years, maybe two years in Indonesia.

And we got back to the Philippines because my wife's health condition was not going well in Europe. So we decided we go back to the Philippines because you have your relatives and things like that. Actually, she got better afterwards. One of the reasons why she got better is because we bought a farm and we started planting our own vegetables and also took care of our own chickens and also I started fishing again.

I grew up in a farm and the river is nearby. So with that experience, it's like going back to my childhood. So we had this farm and we have the same concept with Denison— sustainability, regenerative agriculture, not forcing nature, you know, to produce. It should be you adjusting to nature rather than nature adjusting to you.

So that's how I met Denison. So actually in the process of finding alternative sources for my wife, we needed to find an alternative for sugar. Because sugar, you don't know where it's coming from. The second thing is it's mass produced and it's like, I don't know what's inside.

Of course, maybe there are some real natural sugars but we decided to look for honey. Sources of honey. So we had our own share of fake honeys. There's a lot in the Philippines.

But during the course of four years, we were searching for the real honey. And funnily enough it's just our friends [who] were actually selling honey in the market. And, you know, the way they sell honey in the Philippines, or in Bataan specifically in our place is... we just put it in a San Miguel bottle— the bilog. Bilog or the lapad and you know, it's not really presentable. If you go to Bataan and you find this bilog or lapad, which is on the roadside, you would not buy it or you would not think that it's the real authentic honey. So we were consumers of the honey for four years, or three, or four years.

And then afterwards, I had this idea that maybe we can help more rather than just buying ourselves. We can help them sell their honey because I was asking them how they… the honey and they said that they just sell it in the roadside.

One sad fact is actually the honey that they harvest in Bataan is sold to somebody or someone in Baguio, for example and they don't label it as Bataan honey, they label it as Baguio honey or Benguet honey or something. And that's really sad because according to them Bataan is not really known for honey for wild honey. Now, that's why I decided when I was doing the packaging, instead of using commercial packaging, I just decided to put Bataan to spread awareness that this honey is coming from Bataan.

There's a lot of stories about how they harvest the honey. Goes back to maybe 30-40 years ago, according to the person that I know. But of course, their grandfathers was doing it before that.

One sad fact is actually the honey that they harvest in Bataan is sold to somebody or someone in Baguio, for example and they don't label it as Bataan honey, they label it as Baguio honey or Benguet honey or something. And that's really sad because according to them Bataan is not really known for honey for wild honey.

Jess: Yeah. I wanted to ask, have you been on a harvesting trip? I'll be honest. I have very little knowledge about how honey is collected, the process. So can you kind of maybe tell us who harvests it and what's the process like of harvesting the honey?

Kabo: Yeah, actually in the Philippines there are more wild honey being harvested from forests and it has been passed down from generations.

And I've been with them once. And I will never do it again because it's so… it's so intense. So it's dangerous at the same time because you go up in the forest, of course. Sometimes these guys, they scout the forest. They mark where the bees are and then they let the bees gather enough honey before they harvest some honey from them.

They don't over, you know, over harvest. They want to make sure that the honey is ripe enough for the harvesting because you can only harvest as much honey during one year, for example.

When I went with them we walked for maybe about two, three hours in the forest. Along the way, they're collecting these leaves and they know the type of leaves that only produces smoke rather than fire. It's better to produce smoke only, because they know the importance of the forest and if they start making a fire, then that will be a disaster.

So they gather these leaves on the way and then they cut some bamboo and with this bamboo and the leaves, they, they tie it together. And then as soon as they reach the, the destination where the hive is, then they start producing the smoke.

The one that we have as wild honey in the Philippines is called Pukyutan or Apis dorsata breviligula. It’s endemic to the Philippines. You cannot find it anywhere else. There's this Apis dorsata in Indonesia or other Asian countries, but the breviligula species is actually endemic in the Philippines and you can only find it in the Philippines.

Jess: So that's, sorry, that's the bee?

Kabo: That's the bee. Yeah.

Jess: Do they have stingers?

Kabo: Yeah, they're more vicious than the normal bees, the the commercial bees. So you really need to be careful. They're bigger, they're more vicious. And they cannot be tamed.

So that's why up to this day, they are wild. If somebody tells you that they're culturing this Pukyutan, you shouldn't believe them because it's very difficult to tame them. They're born to be wild, I would say.

When they start making the smoke the funny thing is this, the bees are actually so high, maybe two-three stories building.

And then normally the traditional way is they have this baging. I don't know, how do you call it in English? The vines, yeah, tree vines which are thick enough to climb on. They actually wrap it around the tree, and then they use the vines to climb up. And as soon as they light up the smoke, somebody's at the top. And then as soon as the bee realizes that somebody's producing the smoke, a big lump of the bees actually fall down straight to the ground.

And then when it falls down, it disperses afterwards. So you should not run because of course the bees are faster than you. So you take cover in the area where there are smoke. So you stay there, in the smoke area so they will not attack you. If you start running, then of course there's no smoke and then they will be able to get you and sting.

I've done it once. I'll never do it again because I was one of the guys who started running.

The one that we have as wild honey in the Philippines is called Pukyutan or Apis dorsata breviligula. It’s endemic to the Philippines. You cannot find it anywhere else.

Jess: Did they warn you about the process?

Kabo: Yeah, because they are my friends. So, I mean as I said, they warned me, you know, and said, you should stay in the area where you have smoke.

The first time I did it, I was so afraid. A lot of bees circling around, I started running. So it's really dangerous stuff.

Jess: How long usually, for example, if you have to hike through the forest… how far of a distance usually do you have to hike to get to where the wild honey is?

Kabo: It depends. Actually, in Bataan, the forest is very close. So sometimes you will find a hive just one kilometer, two kilometers away. But further, for example, you can find a hive or something 30 kilometers away. So sometimes they just camp or they have their tents. They go to the forest. Of course, they know the directions. They've been doing it for a long time, so they know where they go in the forest. So maybe you walk for 30 kilometers or something. And it's not a leisurely walk. You need to walk through vines, the tall grasses maybe twice as tall as you. It's really a very slow hike. Sometimes they take five days to one week in the forest just to gather honey.

Jess: That's what you don't hear, right? You don't realize how much work is being done in order to harvest. Especially like you said, with all the fake honey that's out there, right?

I'm curious to know also. So you said there's the Pukyutan. Is there only one specific type or is that the category for all the honeys that's harvested in Bataan?

Kabo: There are different types of bees actually based on my experience here. The first one is Pukyutan. The second one is what they call the Ligwan (Apis cerana).

So there are different types of bees and they actually store their hive very differently. So that's what people need to understand. So we have the Pukyutan, the big ones. The Ligwan and the other one is what we call the Kiyot stingless bees (Tetragonula biroi). Very small, you would mistake it for a fly.

I'm not sure if it's endemic to the Philippines or [if] there's also other varieties of Kiyot here in parts of Asia, but these are very small bees, stingless bees. They also produce honey.

These different types of bees actually produce different types of honey. So for example, the Pukyutan builds their hive outside. They build it on the tree branches so it's exposed. So normally when it's exposed it has more moisture. The flavor is very mild, not so sweet.

So that's that's how the Pukyutan does it. So maybe they, I don't know, maybe it's because of evolution that they're willing to, you know, that they're used to this type of production of honey and they consume it, for example, themselves.

The Ligwan actually hide. So what they do is they hide their beehive.

The Ligwan, it's the same as the one that you see when they have cultured bees. You have this box where the bees actually go inside because it's hidden. So they like it hidden. So for wild Ligwan, normally what they do is they go on dead trees. There's space inside the tree so they build their hive there.

So the difference between the Ligwan and Pukyutan is the Pukyutan has a very thick coat, about 15 centimeters or something. The Ligwan has a very thin coat, about three to five centimeters.

The taste of the Ligwan honey is much stronger and the honey that you get is a little bit thicker because it's stored in a closed environment. Of course, when it's stored in a closed environment, the honey when it's thicker, then it's more sweet.

And also if it has a very... how would I explain it? There's this aroma that you cannot find in a Pukyutan. It's, I don’t know how to explain it actually, but the aroma is a bit stronger.

Jess: So like a sweeter aroma or eathier?

Kabo: Earthier, yeah. And then there's another one they call Kiyot. As I said, it's a very small variety of bee and normally the taste of the honey is sweet and sour. I don't know why.And when you taste it, it's like there's a little bit of vinegar taste on the honey. But the Kiyot normally doesn't produce a lot because they're very small.

So normally the honey gatherers prefer the Pukyutan because they have a very big comb and they can harvest more from it and the taste is actually very flowery, not so sweet, so a lot of people prefer the Pukyutan, in the Philippines, compared to the Ligwan.

Jess: Yeah, that's interesting to know the differences in the taste and even the consistency or the thickness of the honey. Are there traditional or indigenous ways that they use or prepare the different types of honey? Or they just eat it by itself?

Kabo: They're still using the traditional way meaning they gather the comb and they just squeeze it out and that's it. So there's no other processing done.

There's other ways to actually process it, like reduce the moisture for commercial reasons, of course, but what they do in Bataan, they just gather the honey or the honeycomb and squeeze it out. And afterwards, filter it to actually filter the bigger particles. After that, we just bottle it. That's it. That's just like a freshly squeezed orange juice.

Jess: So is that considered, because there's labels here, like raw?

Kabo: Yeah, that's considered as raw unprocessed honey.

Jess: So what's what's the difference, if you know [between] the raw wild honey where they process it like that versus what you find in the market?

Kabo: Sometimes the one that you see in the supermarket, it undergoes this what they call a drying process. So there's, if you search online, we have honey dryers. It's actually a good practice if you want the shelf life to be longer because when you dry the honey, then you lessen the moisture to an acceptable level. I think in the US or in Europe, it's 18% moisture level.

Sometimes for the raw honey, the moisture level is a little bit on the upside, like 19-20% but still fine. I mean it doesn't expire or it doesn't go stale for a longer period of time. But of course, if you want the honey to be on the shelves for maybe five, six years, then you need to reduce the moisture a little bit just to avoid fermentation.

But in any case, I think based on experience, I bought honey and I stored it for one year, two years, and then we consume it afterwards and it's still fine for the raw one.

As long as you don't harvest it during the rainy season, because during the rainy season there's a lot of moisture present. So if it goes let's say above a certain level of moisture, then it will start fermentation. And it'll become a little bit sour.

Jess: So the rainy season is considered off season for harvesting. So when is usually in-season honey?

Kabo: In-season would be when there are a lot of flowers around. So for example, in the Philippines, the sources of flowers are flowers from trees. Recently in April, the first few weeks of April are actually the season for Narra, also kasoy—cashew nuts—in Bataan. Also mangoes, they produce a lot of flowers.

Now, actually, we're going to end of April, beginning of May, there's this tree— they call Tanguile, like a native mahogany but it's endemic in the Philippines. I'm not an expert, but according to the hunters, the Tanguile tree produces flowers only once in every 4-5 years.

So it's a lucky year this year because when the Tanguile flowers, it produces a lot of flowers and there's a lot of nectar that's gathered from this tree. So it's a lucky year for them.

If you go to the forest during the rainy season, it's also not ideal. It's very dangerous, more dangerous during the rainy season. So maybe it's one way of nature, you know, wanting to recuperate.

Jess: Did you notice a difference in the taste of the honey? Because I don't know if it differs depending on what's blooming, what's available in the area. So I think that's kind of fascinating.

Kabo: Actually it differs every month. Because it depends on the type, as you said, it depends on the type of flower.

So for example, the Narra, it produces a very yellowish honey when the bee gathers them, and it's a bit floral. And sometimes the season of the Narra tree and the mango tree coincides with each other. So that's my favorite for the moment.

I've tasted the Narra with the mango and you have the floral and a little bit of this citrusy flavor. That's my favorite so far. And also the favorite of my wife. It's different every time.

Sometimes the season of the Narra tree and the mango tree coincides with each other. That's my favorite for the moment.

Jess: It sounds so delicious. I wish I could just transport there right now. You mentioned kind of earlier, I think when we were first chatting, the harvesters, before you came in, where were they distributing? Or was it something that was just staying in Bataan locally or it's hard for them to find or to distribute it beyond the barangay to the city?

Kabo: For them, sometimes it's difficult, sometimes it's not because there are seasons when they have fires.

But there are also seasons where they couldn't sell their produce. For example, right now, the Tanguile tree is really blooming, they said. And it produces a lot of honey and they need to find other ways to actually sell the honey that they gather.

So there are years where they have a lot and then there are years where they harvest a very small amount.

As I said, they have these customers in Manila or Baguio, sometimes they label them as Davao honey because Bataan is not really known for honey production.

People of course don't just trust you when you sell or when you market pure honey because they have experiences already buying sugar honey mixed with calamansi and they market this as real honey.

As I said, they have these customers in Manila or Baguio, sometimes they label them as Davao honey because Bataan is not really known for honey production.

Jess: Yeah, so that's what's interesting. If the public is used to this fake honey with maybe flavor, maybe that's the honey "flavor" that they're used to. So when they taste something different that's actually raw and wild, they may think, oh, this is not real honey because this is the honey that I'm so used to consuming.

So that is really sad. That makes me really sad.

Kabo: We're creating a little bit of awareness, actually, and sometimes Google is not helping. You have this fake honey test out there where you have a matchstick, you put it in the honey, and when it lights up, then it's not fake. When it doesn't light up, then it's fake.

But actually based on experience, I actually squeezed the combs directly and then I had two tests. I tried, you know, the match the principle, one lighted up and one didn't light up.

So it really depends on the on the moisture content present in the honey. So, of course, it can be a quick test, but it's not an assurance that honey is real or pure. So of course when you manufacture a "fake" honey, you know, all these tests at Google, then you start, for example, for the sugar, when you make a "fake" honey, then you make sure that the matchstick lights up.

There's a lot of tests out there which are not not real. There's this even one absurd test that's saying that if you have a real honey, then it will not attract ants. Which is, of course, very false, because I mean, if you have a sweet stuff lying around then, of course, ants will get it.

Jess: So is there any way to tell if it's real or not or you really have to trust your source currently in the Philippines?

Kabo: The only test actually is based from some beekeepers that I know. You can do an authenticity test, which you need to undergo a check in Manila or the only office that you can actually test the authenticity of the honey is in Manila.

I forgot the name, Philippine Nuclear Research Institute or something.

And of course, it's not so cheap. I don't know what the price is, but if you want to test every batch of the honey, then of course you would lose a lot of money testing. So one of the things maybe that can really help producers of honey would be to make this test really affordable so that they can really prove that it's pure.

Jess: Right. Well, if you have to pay for authenticity, that's another obstacle or barrier to accessing the raw, wild honey.

So that's all great stuff to know. Thank you for sharing, yeah, all of that. I know that our time is running out, but is there anything else that you wanted to bring up about the honey and where people can buy it right now, maybe, if they're interested?

Kabo: Well, actually, for us, it's not about making profit out of it. It's more on helping them and also raise awareness that you can actually buy pure honey from Bataan. Maybe the best advice is when you're buying honey online from somewhere, you need to really do a little bit of true diligence maybe the first time you buy it. And make sure that there's a real source of honey from the bees or from the people who you buy it with.

For me, I'm supporting all producers of real honey because at the end of the day, it should be them that should profit from it, you know, rather than other people who who produce this fake honey out there. So as long as we can build again the trust, you know, from the customers I think it's a win-win for all.

Jess: Awesome. I learned so much. I really hope there is a way that, you know, not just to make money, but to preserve this way of life, of tradition. And just letting people know that we have such a variety of honeys that exist. Thank you, Kabo, for your passion and your drive to bring awareness about Philippine honey.

Share this post