A Language of Gratitude

And how it shapes the way we see the archipelago’s food landscape

Hello, and welcome to another meryenda Monday. There’s been an influx of new subscribers, both from the Philippines and the US. Welcome! I’ve been on a bit of a hiatus since moving back stateside after a year-long journey in the Philippines and am easing back into regular monthly posting.

In the next few months, I’ll be sprinkling in a recap of my Philippines experiences and recommendations (ie. farm stays, suggested food itineraries) on top of the essays. I’ll be integrating the chat function on Substack, somehow, to extend the conversation on some of the essays.

Next Monday, we’ll be releasing a meryenda minutes episode with Kabo of Hagdanan Farm in Morong, Bataan and his advocacy for local wild honey gatherers as well as the blurry designations of Philippine honey— is it really honey?

Currently, meryenda is a reader-supported independent publication. If you find value in our work or use it as an educational resource, consider becoming a paid subscriber for $5/mo or $48/year. If you’d rather make a one time donation, please reply to us directly so we can work something out. Your contribution allows us to nurture this space such as commission works from our community. Salamat 🫶

A Language of Gratitude

During my stay in the Philippines, I amassed a collection of books by Filipino authors and publishers. One is Lawrence Ypil’s poetry collection, The Experiment of the Tropics. There is a chapter titled “There are Fourteen Ways” in which one of the lines goes like this:

"She lived on a diet of fish. There was a chair but she didn’t sit on that.”

I found myself rereading these observations, allured by the blunt ambiguity splayed on the page. Is it the author’s use of hollow language that magnifies the erasure caused by imperialist legacies? Ypil’s work recollects moments in Philippine history during American occupation. In intentionally using vague words such as fish and that, perhaps he cautions: in learning a new language, we also unlearned our own.

Ypil’s poetry collection reminds me of Robin Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, a book I find myself returning to repeatedly. In the chapter “The Grammar of Animacy,” a word forever shifted my perception on language: puhpowee. Kimmerer so eloquently describes,

“In the three syllables of this new word I could see an entire process of close observation in the damp morning woods, the formulation of a theory for which English has no equivalent. The makers of this word understood a world of being, full of unseen energies that animate everything. I’ve cherished it for many years, as a talisman, and longed for the people who gave a name to the life force of mushrooms. The language that holds Puhpowee is one that I wanted to speak.”

The potency of language evolved into a recurring thought when I began researching tapuey and sought more ways to describe it. While I understand Tagalog, I can’t speak fluently (despite it being my first language)— enough for casual conversations and to etch questions surrounding food.

Tapuey (bayah in Ifugao) [n.] a traditional fermented rice beverage commonly consumed in the highland areas of northern Luzon, also referred to as rice wine

I started listening (and I mean really listening) to the people around me, most especially to the slips of their food idiosyncrasies: fondness for a particular rice because of its nutty aroma, desire for the first press of patis and all its golden glory, tinola simmered only with native chicken because of its incomparable depth of flavor. I realized the richness of our food landscape in the way Filipinos describe nuance. What else lies in this vocabulary ineffable in English?

Patis [n.] fish sauce

Tinolang manok [n.] chicken cuts boiled in hot water and mixed with slices of vegetables, traditionally that of papaya, chayote (vegetable pear), upo (bottle gourd), malunggay (moringa), or sili (chili) leaves

Take, for example, the word minamis-namis described in Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture by Doreen G. Fernandez:

“There is another sweetness… the slight, mild sweetness to be found in non-dessert foods— like a papaya at the right stage of firmness, or certain varieties of banana, or young coconut at a precise stage of softness, or even a very fresh heart of palm (ubod), or a fish just out of water and made into kinilaw. Manamis-namis is a subtle, fresh sweetness hidden in the food’s essence, tasted after and within sourness or bitterness, a flavor principle learned by the Filipino from his environment and one invisible perhaps to the non-native.”

In Filipinas Journal Volume 3, in describing cooking rice in the Mountain Province, there is a word for the final stage called in-in:

“The last step is the most crucial, this quiet steeping in the heat. What it means is that rice will not be hurried, that it requires its own time to swell and sweeten… There is loveliness in the word. Anyone who has ever cooked rice to perfection realizes the beautiful stillness that is this final phase. In the stillness of waiting is a lesson of patience.”

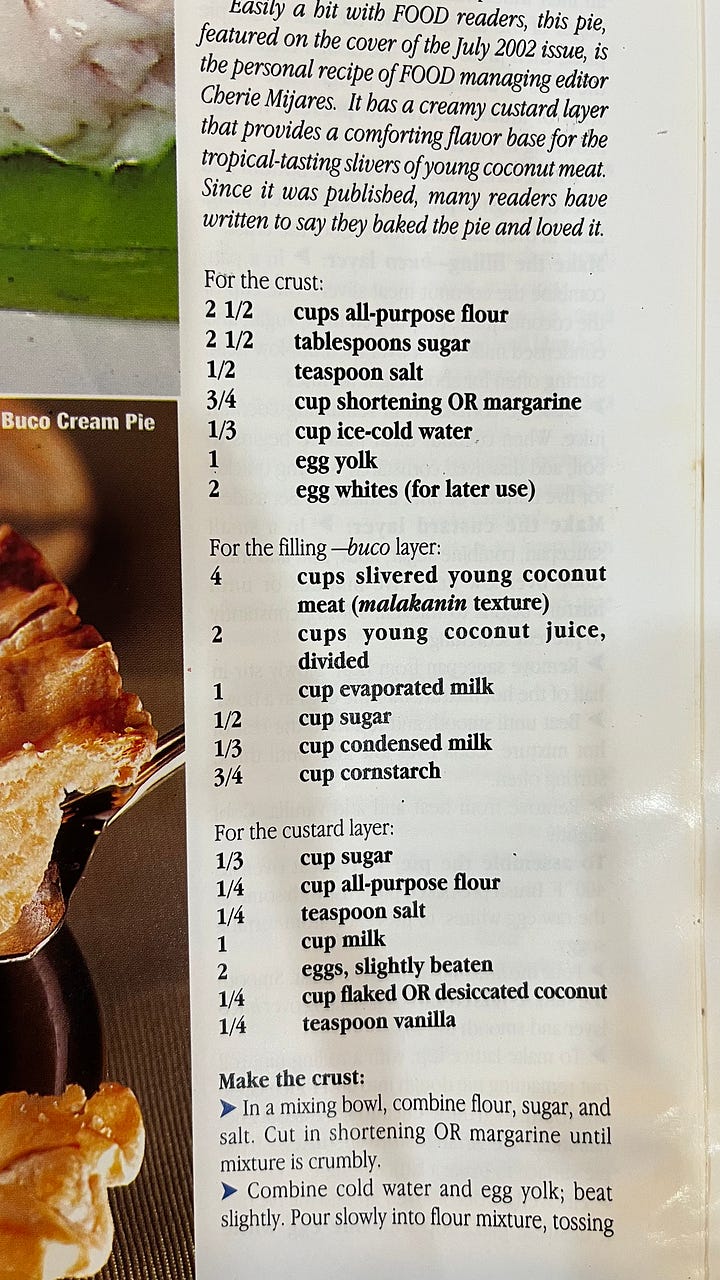

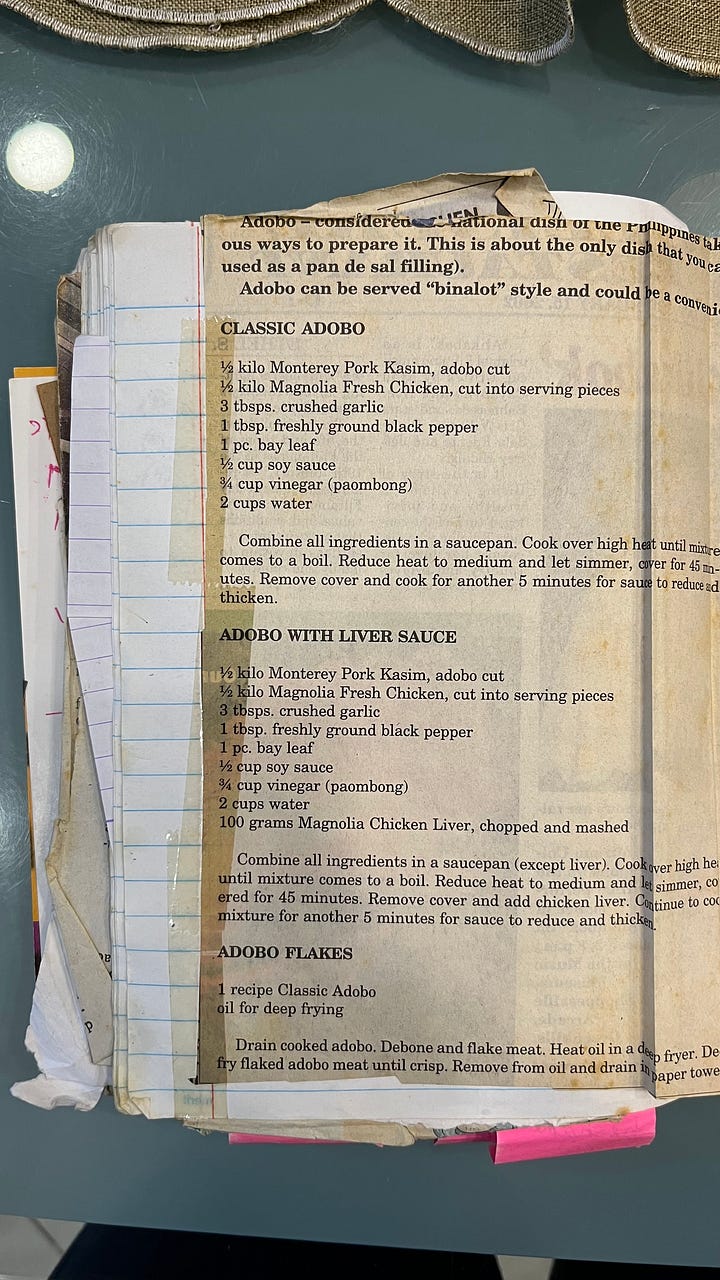

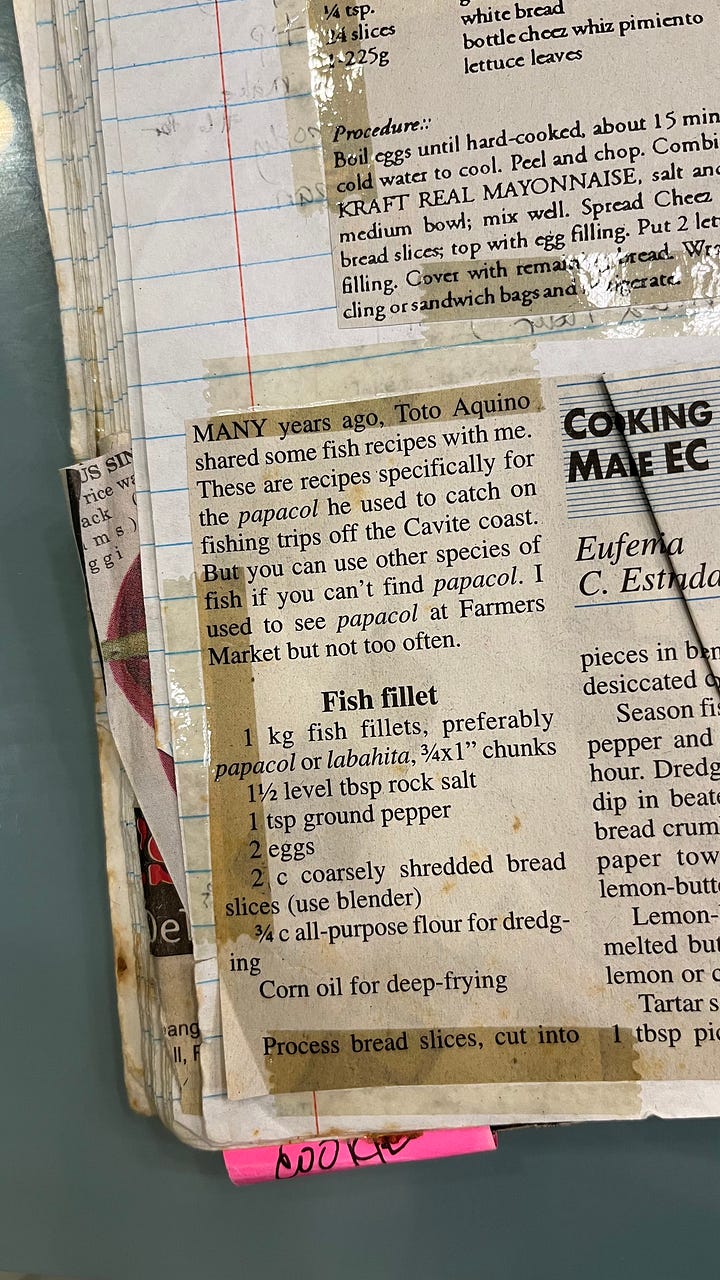

I stumbled upon a pile of 2000s Yummy issues— a Philippine printed magazine and online platform dedicated to food— in my tita’s cabinets containing recipes listing distinct ingredients (mind you these are suggested menus tailored for home cooks).

Use fish fillet, preferably papacol or labahita.

Use paombong vinegar.

Use lakatan banana.

Use slivered young buko meat (malakanin texture).

While some recipes such as bananas foster or buko (coconut) pie are influenced by Spanish and American occupation, Filipinos assert their expertise on Philippine produce with their emphasis on specificity. How else can one name maturity levels of a coconut without paying special attention to the portrait of the natural environment? In fact, according to the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, the coconut industry classifies coconut meat based on words from the Tagalog language:

“Malauhog (literally "mucus-like") refers to very young coconut meat (around 6 to 7 months old) which has a translucent appearance and a gooey texture that disintegrates easily. Malakanin (literally "cooked rice-like") refers to young coconut meat (around 7–8 months old) which has a more opaque white appearance, a soft texture similar to cooked rice, and can still be easily scraped off the coconut shell. Malakatad (literally "leather-like") refers to fully mature coconut meat (around 8 to 9 months old) with an opaque white appearance, a tough rubbery to leathery texture, and is difficult to separate from the shell.”

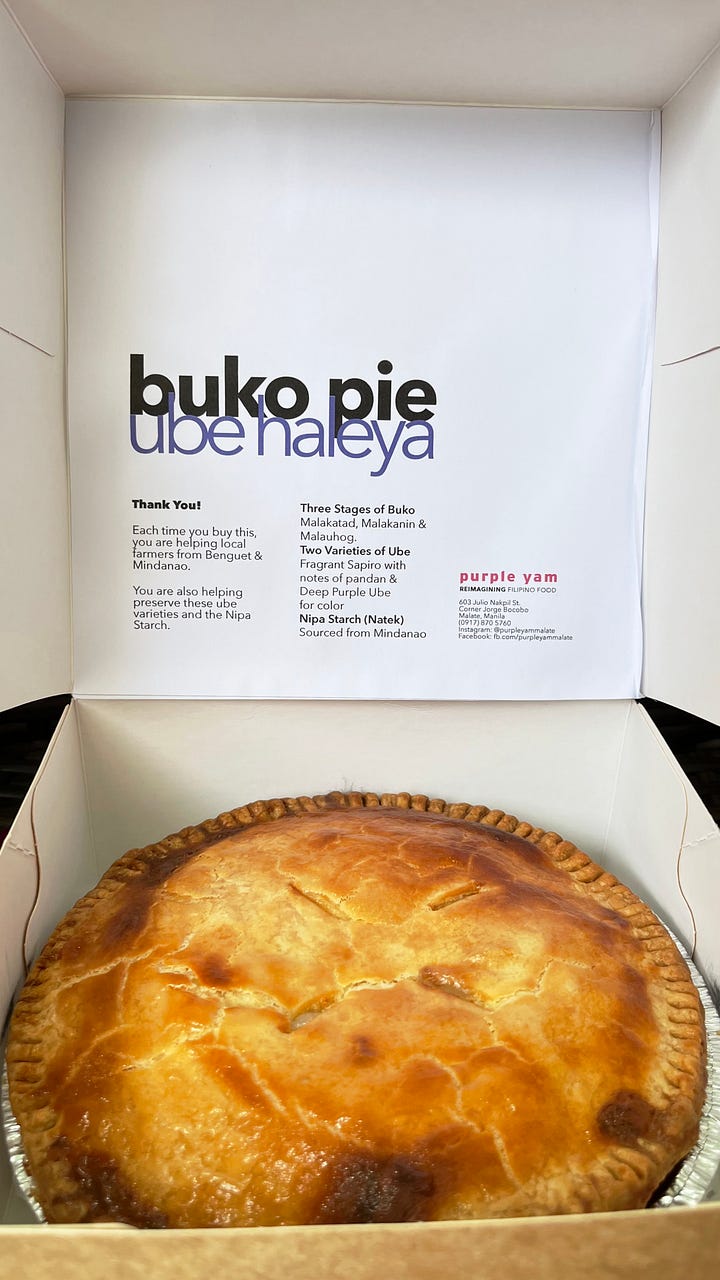

In today’s world where varietals loom beneath the shadow of monocrops and mass supply, I find this blatant nudge to specificity particularly refreshing. Purple Yam Malate in Metro Manila highlights the coconut’s versatility by incorporating the three stages of coconut—hard, firm, soft—in their ube buko pie. A bite releases the coconut from the constraints of its exoticized sheen, striking one with delight at the fruit’s textural range instead.

In Potluck Hidalgo Bonding (A Family Heritage Cookbook), a recipe for kalamay hati (coconut jam, also referred to as latik in Leyte), simply calls for two ingredients:

6 kg matamis na bao (not casetas)

Kakang gata from 25 niyog, grated and pressed with 1 cup (only!) water

The author then follows up with a note explaining differences among sugars available at the market:

“Note: panocha = matamis na bao = casetas = igual pareho. This is just sugar in its most primitive state, put into different containers. Casetas as distinguished from matamis na bao, is formed in bamboo rings arranged on top of a wooden table. The molasses are poured from a [cauldron] into the rings and allowed to cool. The product is called matamis na bao when poured into empty half coconut shells.”

Compare that to my most recent encounter with a cellophane-wrapped Philippine sugar stamped with an “export quality” badge of approval labeled as “hardened brown sugar candy.” The choice of words, while likely adapted for a broader audience, estranges its origin and diminishes the bounty of traditionally made Philippine sugars. Is panutsa too inconvenient? Too unfamiliar? Perhaps. But the Philippines’ food system has already been shaped by centuries of colonial rule, surely we can collapse these molds and reimagine the archipelago’s culinary contours.

Kakang gata [n.] first extraction of coconut milk from pressing grated matured coconut meat

Niyog [n.] ripe or mature coconut

Panutsa [n.] unrefined cane sugar molded in coconut husks

Is there room for compromise? Consider gochujang’s place on the global platform today— it’s found its way on viral TikTok recipes, Michelin restaurants, and even Shake Shack’s menu. At H-Mart, a Korean supermarket chain, entire aisles can be found dedicated to this Korean pantry staple. A few glossy red tubs flash a description indicating hot chili paste or red pepper paste on its labels; the word gochujang is emblazoned on them all.

This past year, I thought a lot about what it means to write about Filipino food as a second-generation Fil-Am living in the Philippines. What I saw as my downfall inspired me to reflect and what emerged was a personal watershed for Filipino food. How do we intentionally irrigate what’s already present in our environment?

In Ifugao, Irene (a local guide) plucks a leaf from a bushel at the roadside. Blackjack, she tells me. Its scientific name is Bidens pilosa. In many parts of the world, it’s more commonly considered a weed. Yet in Batad, where the magnitude of rice pulses beyond everyday routine, it is coveted for the bubod used to make tapuey; here, they call it onwad.

At Filipino restaurant Hapag in Quezon City, I marveled at the use of native pansit-pansitan as garnish. The small, heart-shaped herb offered a peppery bite, adding snap and sharpness to sinuglaw. At Den and Jean’s Natural Farm in Batangas, I munched on handfuls of pleasantly crisp pipinong gubat (think nano-cucumbers) straight from the vines. While pansit-pansitan and pipinong gubat grow abundantly in the Philippines, they are often ignored, an afterthought to imported spinach and cucumber flaunted at the markets.

It made me wonder, if we knew more about our plants, maybe we would think twice before calling them weeds.

Sinuglaw [n.] a portmanteau of the words sinugba, meaning grilled; and kinilaw, a cooking method by curing in vinegar or other acidic agent

What narratives do we want to construct and carve for the Philippines?

The current general framework of food language doesn’t quite embrace the nuance of the archipelagic landscape. Fruit wine drinkers still place grape on the mantle of the wine hierarchy. Pedronan tapuey, while made similar to makgeolli, is nothing like its Korean cousin: it boasts a translucent amber color, has a nose filled with soy and savory elements, and offers punchy layers of sweetness and tanginess reminiscent of a bite of tamarind candy. The myriad of traditional Philippine sweeteners is reduced to “palm sugar” or lumped simply as “candy.” Coconut and its wealth of culinary applications—think pamapa itum, an aromatic spice paste widely used in Tausug cuisine featuring burnt coconut meat, or the soft gelatinous flesh of macapuno or the edible nucleus of a mature coconut called tubo ng niyog that bursts of crisp apple—wallow behind a shimmering veneer of liquid tropical paradise.

Macapuno [n.] a naturally occurring cultivar with an abnormal development derived from the Tagalog word makapuno— the local name of the phenotype in the Philippines, meaning "characterized by being full", a reference to the way the endosperm in macapuno coconuts fill the interior hollow of coconut seeds

Tubo/tumbong/buwa ng niyog [n.] also called sprouted coconut; the edible spherical sponge-like cotyledons of germinating coconuts

We speak and use language every day; that means we can find abundance every day. Our intention with language can sow more meaningful relationships with what’s around us and lead to more interesting everyday lives. Tucked inside words is the agricultural biodiversity of the Philippines, respect for our farmers who bring us nourishment, connections to our cultural bearers and culinary guardians who are memory banks of a world calling for our attention and care.

When we choose to say Bongkitan rice or Balatinaw rice, we challenge the economic system that favors productivity and efficiency at the cost of the earth. When we choose to say balikutsa or pakaskas or muscovado, we participate in the sustenance of traditional food ways. When we choose to say Bulkan or Latundan banana, we savor the land’s generosity.

Yes, my Tagalog is sprinkled with chords of English. I struggle to blunt Ts, but draw some confidence with the Rs that roll lightly off my tongue. The Philippines’ extensive linguistic diversity echoes the archipelago’s abundance. Embedded within my softened consonants and my too American accent is the world I want to see flourish. I’ve learned, language isn’t a contest in proficiency or pronunciation, but a doorway to worlds of gratitude.

Bongkitan and Balatinaw/Ballatinao/Balatinao [n.] heirloom glutinous rice varieties from the mountainous regions of northern Luzon

Happenings and events from our kaibigan— May 2023

📍🇦🇺🌏 Produced in collaboration between The Entree.Pinays and Erwan Heussaff of FEATR, Cathie Carpio and Mind Society Studios is the The Calamansi Story. Watch the documentary in full on Youtube here. You can also purchase the publication titled The Calamansi Story: Filipino Migrants in Australia at the Merkado Market.

📍🇵🇭🌏 — Ateneo Art Gallery, in partnership with the Philippine Native Plants Conservation Society, Inc (PNPCSI), celebrates 2023 International Museums Day and National Heritage Month with a talk, “Philippine Flora Before and After the Galleon Trade.” Free and open to the public both onsite and online, registration required. Registration and details found here. Happening May 18, Thursday from 2-3pm Manila time.

📍🇵🇭 — Join the Slow Food Community of Negros Island for the Earth Markets Negros Islands at Casa Gamboa in Silay City, Negros Occidental. John Sherwin Felix of Lokalpedia will be giving a talk on Food Heritage and Food Biodiversity. Happening May 27, Saturday between 8am-8pm, with the talk happening at 2:30pm Manila time.

📍🇺🇸🌏 —From acclaimed author Michelle Sterling and illustrator Sarah Gonzales, is the beautifully illustrated children’s storybook Maribel’s Year, a heartfelt story recounting the year a little girl and her mother spend in America while waiting for her father to join them from the Philippines. Find the book for purchase here.

ICYMI 👀

A Tapuey Documentary, in collaboration with Erwan Heussaff + FEATR Media

What it takes to make this wild fermented rice brew from the Philippines.

How About Wine from the Philippines?

While most of wine literature and research focus on grape culture, several studies have been conducted to assess the potential of fruit wine. There have been promising results from many fruits familiar in the Philippines: mango, lychee, bignay or bugnay, guava, passion fruit, and rambutan. This leads back to the question that has fired every neuron of my culinary cortex since visiting the province: why don’t we know more about Philippine fruit wine?