How About Wine from the Philippines?

We mean fruit wines and how they can open the dialogue for winemaking. Words by Jessica Hernandez

I guess now’s the best time to announce some news: I’m now living in Manila! Okay, to clarify, I’m here for a year, at most. I still find myself in disbelief at times but the heavy thacks and thuds from fishmongers at the talipapa right outside my window blatantly shout, “I’m in the Philippines!”

I spend a few minutes throughout the day eyeing the market from my window. Soulful Filipino ballads blast midday, likely to fill in the slower pace of the afternoon. At dusk, the conversations liven while motorcycles zoom in and out. I watch, enthralled with the motions of an alternate food system. It still feels a bit strange not waking up to an alarm and rising instead to these tempos of provincial life.

So why am I here? One month in, I’m still quite not sure I can give a definite answer. I’m realizing this question morphs every day thanks to the generosity of strangers and friends.

What I am excited about is to be able to immerse myself in our country’s food— how it was, as it is, and its ever changing interpretation— as a 2nd-generation Fil-Am. There are ingredients and dishes that I rarely (or have never) had access to living in the diaspora, albeit in a country with the largest percentage of Filipinos outside of the Philippines. The first week here, I saw a banana blossom in the wild and had to repress the strong urge to climb up the tree and harvest it— I kid you not. I watched the sun set gracefully in the background and inhaled the reprieve of Tagaytay’s mountainous air instead, like any normal person would.

So here’s to a year of learning from roadside peddlers, palengke vendors, fading family stories, home cooks, farmers— to condense it, I guess that’s about really anyone here who will speak with me. I’m following the advice of friends who told me, “When there’s a chance, just say, sama ako.” Take me with you. Those words, so far, have led me in the right direction.

How About Wine from the Philippines?

I’ll be honest, fruit wine never entered my orbit of interest. If we ignore the Eurocentric bias we have towards food and flavor, I guess you can say I got my hands on calamansi wine entirely because I moved to the Philippines. I had never read about calamansi wine, much less knew it existed. But if grape is a fruit, couldn’t citrus, also a fruit, become wine also?

It wasn’t until I was in Nueva Vizcaya, the citrus capital of the Philippines, that fruit wine caught my attention. Wine is typically made with grapes but has long been made with other fruits, grains, plants and even honey. I’ve drank mead (honey wine) and umeshu (plum wine) more times than there are calamansi wine hashtags but it just never occurred to me that winemaking can extend to the very fruits we consume here in the Philippines.

So when I looked puzzled when my newly made friend, Daniel, asked, “Have you tried mandarin wine?” while on our way to a chicken farm, we hastily made a U-turn to visit Tita Flor.

Tita Flor and her family produce and process citrus in Solano in the land-locked province of Nueva Vizcaya. She was excited to answer our questions on citrus wine production, but as my questions became more elaborate, she referred us to Dr. Perlita Tiburcio, a food scientist and educator who earned her PhD in food science at the University of the Philippines Diliman. While we were able to contact Dr. Tiburcio, finding her was not as simple as typing an address into Google Maps.

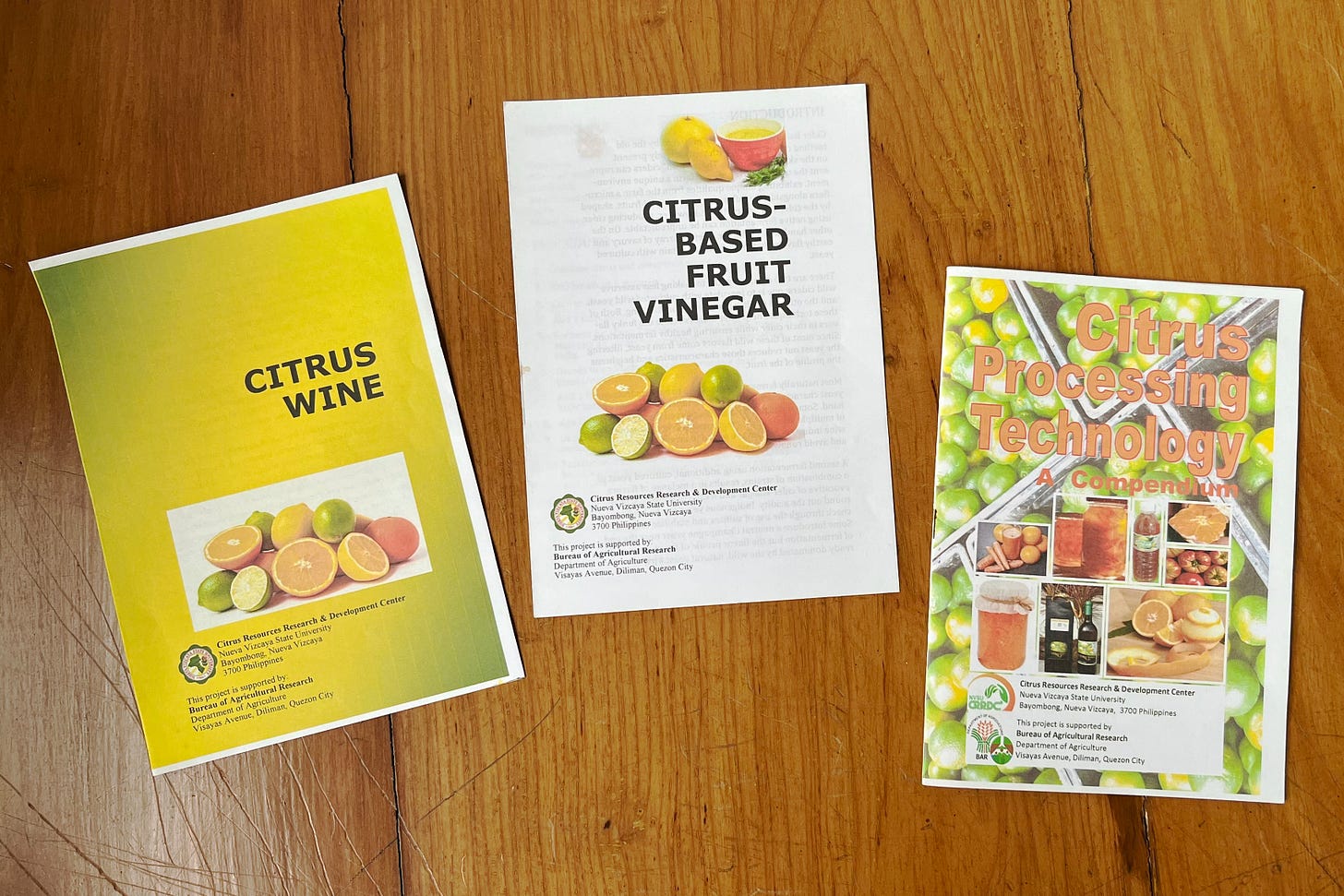

“Dito ba si Ma’am Perlita? Is Ma’am Perlita around here?” my friend, Patricia, asked a roadside vendor, a young boy on his tricycle, and few others around the barangay. With neighborhood locals literally pointing us in the right direction (and a series of U-turns and backtracking), we found Dr. Tiburcio’s home up a narrow hill, her sitting in the front atrium, ready with bottles of fruit wine, citrus vinegars and dusty research pamphlets (that I excitedly read).

According to the 2006 edition of Science and Technology of Fruit Wine Production, wine is defined as “made from complete or partial alcoholic fermentation of grapes or any other fruit.”

Any.

Other.

Fruit.

If wine can be made with other fruits, why is grape wine the most conventional? Grapes actually contain the most ideal balance of sugar, acid and tannins to produce stable wine. Jose M. Mendoza, formerly a scientist and professor in Industrial Microbiology, Food Technology, and Fermentation Technology at Manila L. Quezon University in Quezon City, investigates several fruits in Wines, Liquors and Similar Products. In it, he describes:

“The casoy is pulpy and contains less sugar; the ducat is large-seeded and less pulpy; the guava is heavily seeded; the bignay is seeded with less sugar; and the pineapple is juicy but fibrous.”

Another analysis notes that fruits can be more challenging particularly due to:

"Difficulty in extracting the sugar from the pulp of some of the fruits, or finding that the juices obtained lack in the requisite sugar contents, have higher acidity, more anthocyanins, or have poor fermentability.”

I barely passed my micro course in my university days so I interpret this as: no grapes, more problems.

While most of wine literature and research focus on grape culture, several studies have been conducted to assess the potential of fruit wine. There have been promising results from many fruits familiar in the Philippines: mango, lychee, bignay or bugnay, guava, passion fruit, and rambutan.

This leads back to the question that has fired every neuron of my culinary cortex since visiting the province: why don’t we know more about Philippine fruit wine?

Fruit winemaking as a craft in the Philippines is still in its infancy. The main players mobilizing non-grape winemaking are the very same ones who have little choice in the matter: farmers.

Per Dr. Tiburcio, winemaking is a way to reduce post harvest losses and add value in food processing, or what the West tends to glorify as zero food waste processing. While major supermarkets in the US are praised for investing in new technology to reduce excess inventory, local communities in Cagayan Valley are already championing zero waste processing with little to no institutional support or funding.

So why then, do we glorify these “innovative” solutions for problems we’ve created ourselves? At best, they paint a veneer that ignores the efforts being done at a local level. At the farms, it’s not labeled as innovation, it just makes sense.

I don’t want to be that person harping on the places we get our food. I understand that every point of food access—from the talipapa (wet market) down the street to the neighborhood Seafood City—plays a role in the communities it serves. For those who are able to think about food beyond nourishment, I’m here to agitate where our preferences lie. What we don’t see on the shelves matters just as much as what we do. Maybe it’s more about the questions we ask that allow us to shift away from the default.

Why don’t we see certain products? Who controls the chain? How do invisible hands affect our choices for what we consume?

—

Fruit wine isn’t meant to replace our beloved Cabernets, Tempranillos or Gewürztraminers (had to throw in the wine I’ve been digging with chicken inasal) but it can shift the needle on what winemaking is and what it can be.

I think about wildfires in Northern California and the surrounding vineyards. I think about climate change and how it’s shifting the latitude of optimal winemaking regions. Sustainable and local are buzzwords in the global North, yet they’re ways of living in the global South. When the country’s climate is more suited for fruit trees and orchards, how do we start looking at wines made from other base ingredients with more thought and care?

It’s a given we first need to start seeing value in our locally produced beverages. While I hate to admit it, taste is the biggest factor when introducing these fruit wines against traditional grape wines. You can get someone to try something, but it has to taste good before the conversation can go any further. Fruit wines, justifiably, don’t have the best reputation; they tend to lean heavily on the sweet side, diffusing any complexity rather than conveying characters of the fruit.

I find this as an opportunity to explore what fruit winemaking can be. What happens if we begin dialing into different steps of the brewing process? How can it pair with food or be transformed in a dessert? Will premium grade fruits affect the nature of the wine? What happens when we use locally isolated yeasts? Can fruit wine evoke a sense of place like its more mature grape siblings, Bordeaux and Chianti?

In Tikim, page 13, Doreen Fernandez writes:

“Considering the wealth of Philippine pulpy fruits, we can generate a whole line of fruit wines that could stun the world—all of them, however, sweet wines that go with dessert (after dinner), not dry wines that might go with the meal.”

With education and innovation, what’s currently viewed as a practice to lessen waste can also catalyze into embracing our rich fermented food culture. Fruit wine is nowhere close to a panacea for global warming or food waste, but it can widen the universal dialogue for winemaking— one in which the industry is more inextricably tied to the land’s generosity and one in which the global wine matrix recognizes the vitality of pineapple, mango, chico and bignay wines.

Currently, I’m drinking calamansi wine and while a bit more tart and syrupy than my usual preference, I do appreciate the layers of locality and seasonality and resourcefulness. This bottle may only have cost me 120 pesos (roughly less than $3 USD equivalent) but it has somehow rattled my relation with wine more so than any $30 bottle of Pinot Noir I’ve consumed, however ethically sourced or biodynamic it may have been.

I will say I long for the moment we are presented with a digestif menu and see Cagayan Valley citrus wine or Guimaras mango wine alongside Tawny port. I also realize that at the end of the day, I’m neither a winemaker nor a farmer; I’m just someone who writes and it’s easy to scribble down lofty fantasies when you’re glued to a keyboard. But perhaps writing can at least change people’s relationships with food, hopefully for the better. At the end of the day, I can say I’m okay with that.

PIKA PIKA: Native Garlic

Introducing PIKA PIKA (or small bites in Tagalog), a section I’ll be dedicating to cataloguing ingredients + food in the Philippines.

I’m cooking more with native garlic (pictured on the right), a smaller but much more robust and flavorful garlic than the ones I use back home. Throw in just two or three cloves in a pan and the aroma really kicks in. Most native garlic comes from Batangas, Ilocos, and Batanes and is priced higher than imported ones from China (shocking, but also not). I’m already imaging making a confit… which I’d love to spread on toasted pandesal 🤔 Will report when I do. If you have any thoughts on cooking uses, feel free to leave a comment and I’ll shoot a video to share on Instagram!

In Case You Missed It 👀

The Last Vestiges of Philippine Sea Salt

One day, Philippine salt can silently fade into another cultural artifact. We’ve lived without Philippine salt all this time so why care now when finely ground salt is conveniently within our reach?

Coffee conversation in the West is being driven to address equitable systems; words like fair-trade and organic, while applaudable, fail to look at the chronic illnesses within the coffee industry.

Where Does Ube Really Come From?

As a generation accustomed to store-bought ube jam, we’ve unknowingly detached ourselves from ube’s genetic diversity; canisters and packages have erased local cultivar names such as kabus-ok, tamisan, binanag, and binato from conversation. Even color variations — ranging from marbled white-purple to deep violet — are eclipsed by a defining alluring purple that paints every ube reincarnation.

I’ve avoided buying wine for three years by making all sorts of fruit “country wines”, the good ones are lovely; ginger lemon, mulberry, some are so so, sometimes good; wild banana, guava. Will try dalandan soon with our next harvest. The wines that aren’t so good I turn into vinegar

Great write up. Two thumbs up 👍👍