Part 2 of 2 in this Philippine sugar series.

Hello, and welcome to another meryenda Monday. You’re currently on the free list, and we’re happy to have you here! Currently, meryenda is a reader-supported publication. If you find value in our work or use it as an educational resource, consider becoming a paid subscriber for $5/mo or $45/year. If you’d rather make a one time donation, please reply to us directly so we can work something out. Maraming salamat 🫶

The Peculiar Life of a Buri Palm

I recently returned from a two-week trip across the Visayas, which, by the way, had the most transfers of any trip I’ve planned. Having lived on a large coastal mass of land most of my life *ahem California* my choice of transportation has always been a vehicle on wheels. So far, it has been sufficient for local travels. That has made me a mere reptile in this vast oceanic world. In the Visayas, the islands are close enough to conveniently travel by ferry, so we grew some gills and quickly familiarized ourselves with ports and ferry routes.

Our first stop was Iloilo City on Panay Island. Besides checking off my food list of Ilonggo specialties like pancit molo, laswa, and La Paz batchoy, I also informed my companions to keep a lookout for a few local sugar delicacies: pulot, butong-butong, and kalamay sa buri.

I was particularly interested in kalamay sa buri because of its base ingredient: palm sap.

While palm sweeteners are often grouped under one category, there are actually some nuances worth mentioning. Palm sugar covers the breadth of the palm tree family (there are roughly 125 palm species in the Philippines, most of which are endemic)— the most ubiquitous in the Philippines are nipa palm, buri palm, and coconut palm. Surprise, palms are diverse and are not a monolith! In fact, I just learned the names of the most common palm species in Southern California: the thick-trunked California fan palm and its tall slender cousin, the Mexican fan palm.

So going back to kalamay sa buri. As you might have guessed from the name, this sugar delicacy is made from buri palm sap. Before I delve into our palm sugar delicacies, one should first get to know the peculiar life of a buri palm. Buri palm have been documented to thrive for 30+ years. It is only when it starts to flower that its sap can be tapped to be harvested (by a mangagarit or sap harvester). A buri palm blooms and bears fruit only once in its lifetime and this transition suggests its final years (note: harvesting sap does not shorten its lifespan when locals tap the trees in a non-destructive way). The buri palm’s swan song was so moving that a 1965 ethnographic study in Barrio Caticugan, Negros documented a local resident’s poem dedicated to this phenomenon:

Nanahon sa kilapay; nanalingsing sa kasakit; namunga sa kamatayon.—Buli

It leafed in happiness; it budded in sorrow; bore fruit at death.—Buri palm

I bring up this one very obscure fact not to throw kalamay sa buri in the sphere of scarcity. Rather, I find the life of a buri palm an expression of overwhelming generosity. Imagine, the tree’s life in its sap! In a world that craves efficiency, one might say, kalamay sa buri takes too much time and is not practical. From the decades it takes for buri palm to mature and harvest to the long hours of stirring— indeed, a lot of time is spent waiting. Yet, when I hold this woven parcel, I see the bounty of the buri— its leaves, its sap, the delicate hands and knowledge of the mangagarit— and I am grateful. I wish for more of us to relish in these gifts and to see our palm trees as gifts themselves, rather than objects for consumption. Perhaps we can begin by retelling and magnifying our stories of the buri, just as we do with the sakura and redwoods. Maybe then, we’ll write poems of the buri once more.

So while we ponder on palms, let the sugar wormhole begin.

Philippines Sugar Map

This sugar map focuses on native, unrefined sources of sugar. The two main sources of sugar in the Philippines come from palm and sugarcane.

Palm Sugar

Pakaskas

In southern Luzon, specifically Isla Verde, Batangas, is a palm sugar called pakaskas. Isla Verde is saturated with buri palms, which the locals use for a diverse range of applications. Buri palm sap is harvested and cooked for hours until it thickens and caramelizes. The liquified sugar is then placed in circular containers made of dried buri palm leaves, called casitas, and left to solidify. The canisters are stacked and tied together using buri palm string, making the entire package completely biodegradable. A 2016 study of pakaskas noted that out of the six barangays on Isla Verde, four are engaged in pakaskas production. Pakaskas can be eaten on its own like candy, but the deep caramel flavor provides a complexity that pairs well with kakanin like suman.

Kalamay sa Buri

Similar to pakaskas is the Illongo delicacy, kalamay sa buri, which is noted to be eaten more as a dessert than used as a sweetener. A more detailed observation records the steps in making this sugar. First, buri palm is tapped and sap is extracted usually from the hours of 3pm to 9am at six-hour intervals. This process is called dawat. After each interval, the collected sap is boiled to prevent spoilage. After the day’s collection is finished, the entire batch is boiled again for 3-4 hours until it reaches a dark, sticky consistency. At this stage it is known as pulot or jam. Like its Batagueño cousin, the finished product is then stored in a container made of dried buri leaves called pinadakan.

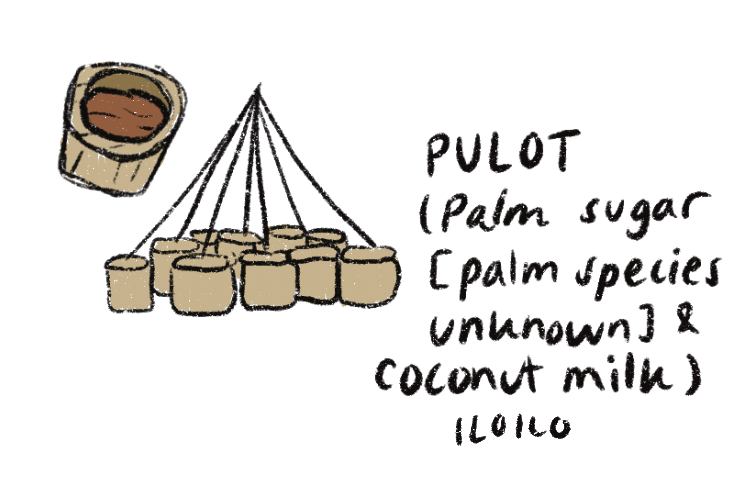

Pulot

Pulot is a viscous syrup similar to molasses found in Iloilo. Sources say it is made either with melted palm sugar or muscovado sugar and mixed with coconut milk. It is stored in bamboo jars covered with dried banana leaf. Peddlers can be found carrying poles with the hanging pulot around Iloilo. It is also most commonly eaten as dessert, but can also be used as a sweetener.

Sugarcane

Balikutsa (balicucha), also see butong-butong and tira-tira

This palmier-shaped sugar hails from the Ilocos region, although this base method of sugar-making is found throughout the Philippines. First, sugarcane is cut and its juice is extracted (through crushing) and boiled in large vats called kawa until it thickens and caramelizes. The sticky mass is then hand-pulled and stretched repeatedly until the color changes into a creamy white. The lengthened pieces are portioned and shaped into its most-recognized shape. While great as a sweetener for kape, it is still popular as a candy treat among children in Ilocos. Most balikutsa on the market comes from the sugarcane farming communities in Sta. Maria, Ilocos Sur. (Note: balikutsa is also the name of a coconut toffee in Mindanao).

Butong-butong

A description of the candy in Laua-an, Antique on Panay Island:

“The hot, melted muscovado sugar is then pulled (butong is a Hiligaynon or Kinaray-a word meaning “to pull”) until it becomes whitish in color and then hardens to create a solid, soft and chewy candy. It is sometimes stretched to create different designs.”

Tira-tira

Romola O. Savellon, a history professor from Cebu, desribes in his paper, “Sugar Production in Pre-Modern Era Cebu”:

“The slim candy wrapped in waxed paper was usually sold to schoolchildren by enterprising sidewalk vendors in the past. It consisted of very sticky solidified syrup rolled into a slim stick and wrapped in multi-colored waxed paper or thin Japanese paper. These tira-tira candies were usually cream-colored. In Bogo City, northern Cebu, the tira-tira is called balikutsa.

Sinakob (panutsa de bao, sangkaka, tinaklob, and its many name variations)

Widely used in the Philippines, this unrefined sugar is made entirely from extracted sugarcane juice that is boiled until it caramelizes, then portioned into half-coconut shells to cool. There can be different grades of the sugar depending on the extraction process. I have been told it’s great used in biko or made into a simple syrup for sago’t gulaman and in saging con yelo. Someone from Pangasinan also told me she used to eat rice with chunks of sinakob— simple, but enough to fill the belly.

Pozorubbio, Panagasinan— a method of making kakanin called patupat utilizes the whole sugarcane during production. First, palm or banana leaves are woven to create hollow satchels, similar to puso (rice steamed in woven triangular parcels also called “hanging rice”) in Cebu. The makers then pour uncooked rice into the tiny openings to fill the satchels. The satchels are cooked in a large kawa of boiling sugarcane juice and coconut milk. Sugarcane stalks are burned as firewood. Once cooked, the patupat are hung to cool and the remaining concoction of sugarcane juice and coconut milk is poured into coconut shells to make panutsa.

*Maraming salamat to John Sherwin Felix of @lokalpediaph for also sharing his sugar findings on episode two of meryenda minutes

Projects and events from our community

Isi Laureano, who we interviewed for our adobo piece, recently launched her Tagaytay Cooking Class. If you find yourself in the area, consider booking and learn how to make Filipino dishes using local ingredients.

Nasirig's Great Adventure is an Ilokano-English children's book about a young girl, a lost tablet, and friendship. This all-or-nothing project from Chachie Abara, Cassandra Balbas, and Mario Doropan runs until November 29, 2022. Back their Kickstarter, share their project, or visit the page to find out more.

The Doreen G. Fernandez Writing Contest is still running! This year’s theme is Roots, Fruits and Vegetables. The contest is open to global submissions. Deadline to submit is November 30, 2022.

Pilipinas Journal (PJ) is a volunter-led education lab and open library that centers Filipino voices, roots, and wisdom. They are launching a contributors network, inviting all people with Philippine roots to contribute their voices, works, or stories. Visit their page to learn more or to submit an idea.

Did you know? October in the Philippines marks Philippine Coffee Month and Peasant Month. We encourage you to seek and support your local organizations directing their service around food advocacy.

Have an event, project, or submissions call you’d like to share with our community? Submit it here.

In case you missed it 👀

Sugar may be one of the most commonplace ingredients, but it’s far from trivial. If convenience is the biggest mask of the past, then perhaps curiosity is the biggest antidote for amnesia. The question of unrefined versus refined is an understandable starting point—I guess “sourced using non-extractive capitalistic methods” is a bit much for the every day grocer—but what stories do we learn when we choose to engage outside of usual choices and narratives?

The Last Vestiges of Philippine Sea Salt

One day, Philippine salt can silently fade into another cultural artifact. We’ve lived without Philippine salt all this time so why care now when finely ground salt is conveniently within our reach?

Where Does Ube Really Come From?

As a generation accustomed to store-bought ube jam, we’ve unknowingly detached ourselves from ube’s genetic diversity; canisters and packages have erased local cultivar names such as kabus-ok, tamisan, binanag, and sapiro from conversation. Even color variations— ranging from marbled white-purple to deep violet— are eclipsed by a defining alluring purple that paints every ube reincarnation.

Have a sugar memory you want to share? Have a sugar delicacy you grew up eating but didn't see on the list? What are sugars called in your region? Let us know :) This sugar resource is meant to be ever-evolving as we hear more of your stories.