What’s a Meal Without Rice?

Navigating the present day meal as a Filipina-American. Words and images by Kristine Angeles

As the months go by, we’re constantly exploring how we can extend perspective. While we may be running the platform, we also want to reiterate how meryenda is meant to be a space for all of us. That said, we’re excited to welcome our first guest writer, who also happens to be a dear friend of ours.

I think second-generation diaspora writers have a unique connection to food. What we eat can be the closest thing to what was lost, what we’re missing, and what we’re searching for. Food is the language that needs no translation, yet it opens up a myriad of discussions. Today’s newsletter by Kristine Angeles touches on this ongoing navigation.

When I first pitched to Kristine about writing a piece, her immediate reaction was, “I’m not a writer!” Words may not come as easily for some, but I truly think we all have stories to share. Even more so, I think in our own endeavors to craft our stories, we play a role in preserving stories swaying in limbo, often waiting for the right questions to bridge them into actuality. Can we overcome our own discomforts and self-doubts to share what our parent or parents never had the chance to say? How can we bring forward silenced voices into our spaces?

Another note: we’ll be taking a bit of a break in October —partly due to important life happenings occurring simultaneously and partly due to an exciting collaboration project we’re excited to be a part of launching… today! (Hint ☕ ) More news on that at the very bottom of this newsletter. We’ll be coming coming back in November at full speed, Manila traffic aside. That concludes our obligatory updates. Please enjoy this issue! - Jess

“It’s not a meal without rice,” I’d often hear in the Philippines. My titas always told me meals like pancit or spaghetti are only considered meryenda. Rice is eaten with breakfast, lunch and dinner but as a Filipina American living in Southern California, I often have meals without rice.

The dinner table and kitchen evolve as generations pass, especially if it’s across the ocean —different environment, different ingredients, different intentions. Along with an evolving dinner table, our identity evolves along with it.

So, what does it mean if I’m not eating white rice with every meal? Even more than that, what does it mean that I’m not eating Filipino food every day? Does it make me less Filipino?

When we sit down for a meal, it could just be that: a meal for nourishment. I’ve come to realize that food means nothing until we put meaning behind it. When cooking in my own kitchen and sitting at the dinner table, I am coming to understand that this is a reflection of how my identity has evolved as a Filipina American, and I wonder what it could mean for the generation after me.

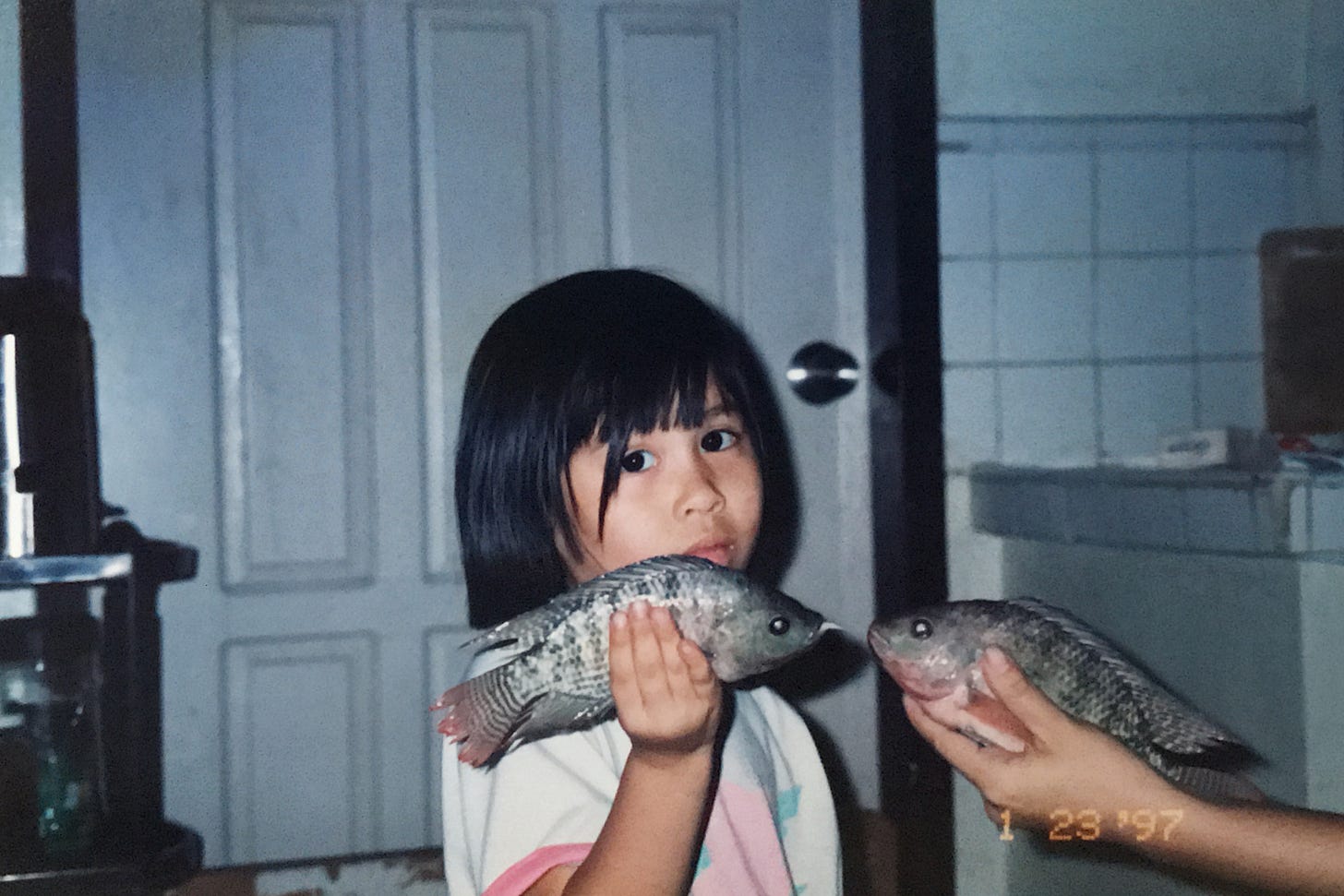

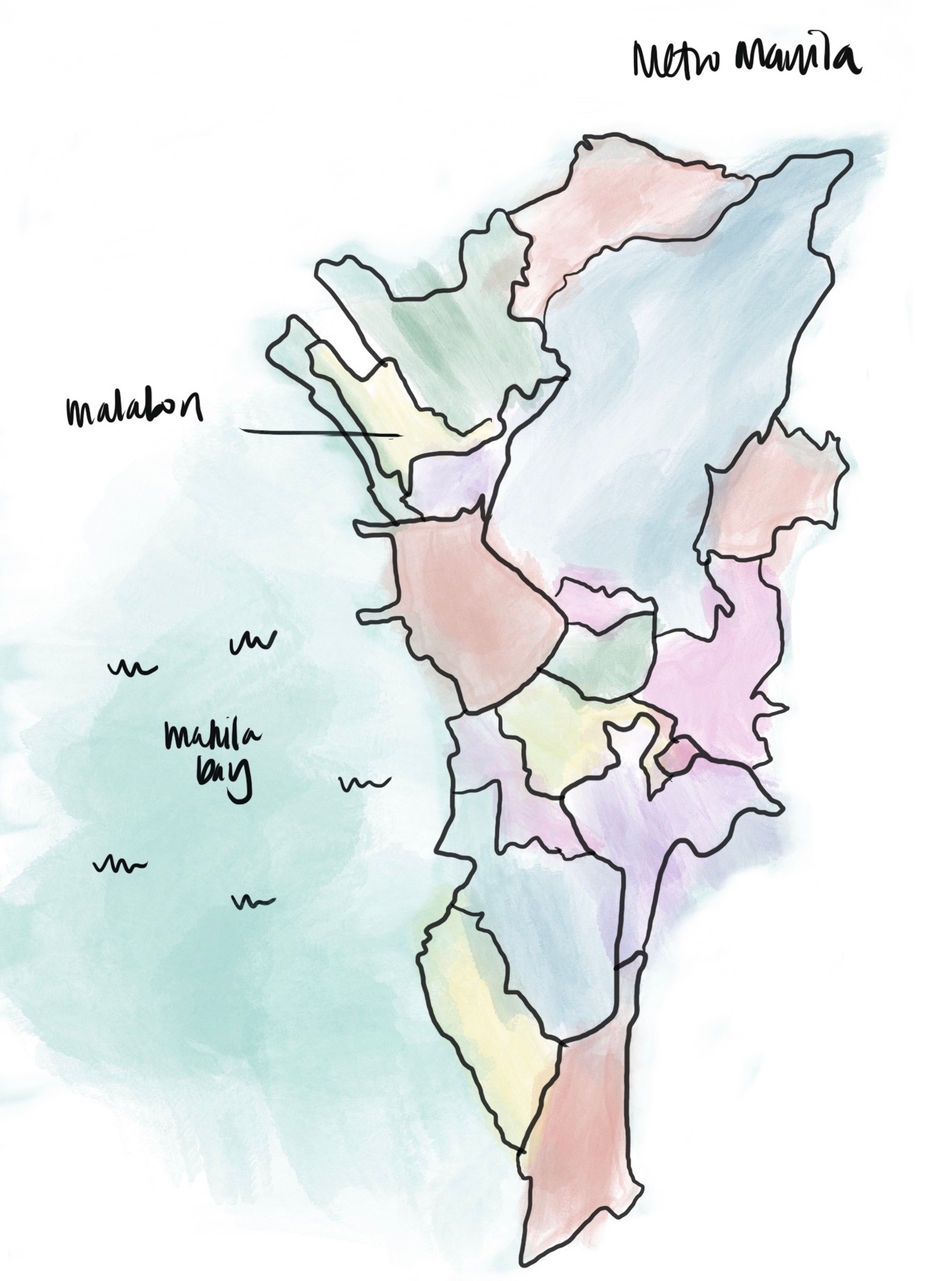

My mom grew up in Malabon, a coastal area in Manila where seafood and fish markets were plentiful. Her nanay would make a trip to the market every day to get food they needed for their family of nine (six kids, nanay, tatay and their katulong or helper). She would bring home different kinds of fish (lapu lapu, dalagang bukid, galunggong), crab, and even oysters by the sack. Their dinner table consisted of seafood dishes like pinangat, along with vegetable sides like monggo or ampalaya, and of course, white rice. Dishes prepared with chicken, pork, or beef were saved for special occasions. Every Sunday, my mom’s lolo would come to eat, and her mom always prepared the best meals that day. One of my mom’s favorite dishes (that I have yet to try) were stuffed crabs.

Unfortunately, my lola passed away before my mom could learn her recipes. My mom didn’t learn how to cook until she was married and living on a U.S. base in Japan. She was thousands of miles away with limited contact to her family. On top of learning how to navigate living in a foreign country, she was entering motherhood with the expectation of feeding her new family. She shared stories of her failed attempts at making dishes from memory. Instead of trying to replicate the dishes her nanay would cook for her, she bought a cookbook from the Philippines and learned the basics: tinola, adobo, sinigang. But her meals were adapted based on what recipe she could find (if any) and the ingredients available to her. Tinola was no longer made with fresh green papaya or other typical veggies she grew up with; she used spinach instead. To make sinigang, she would request packets of sinigang mix as pasulubong when family or friends would visit from the Philippines. She made bibingka and puto with Bisquick flour mix.

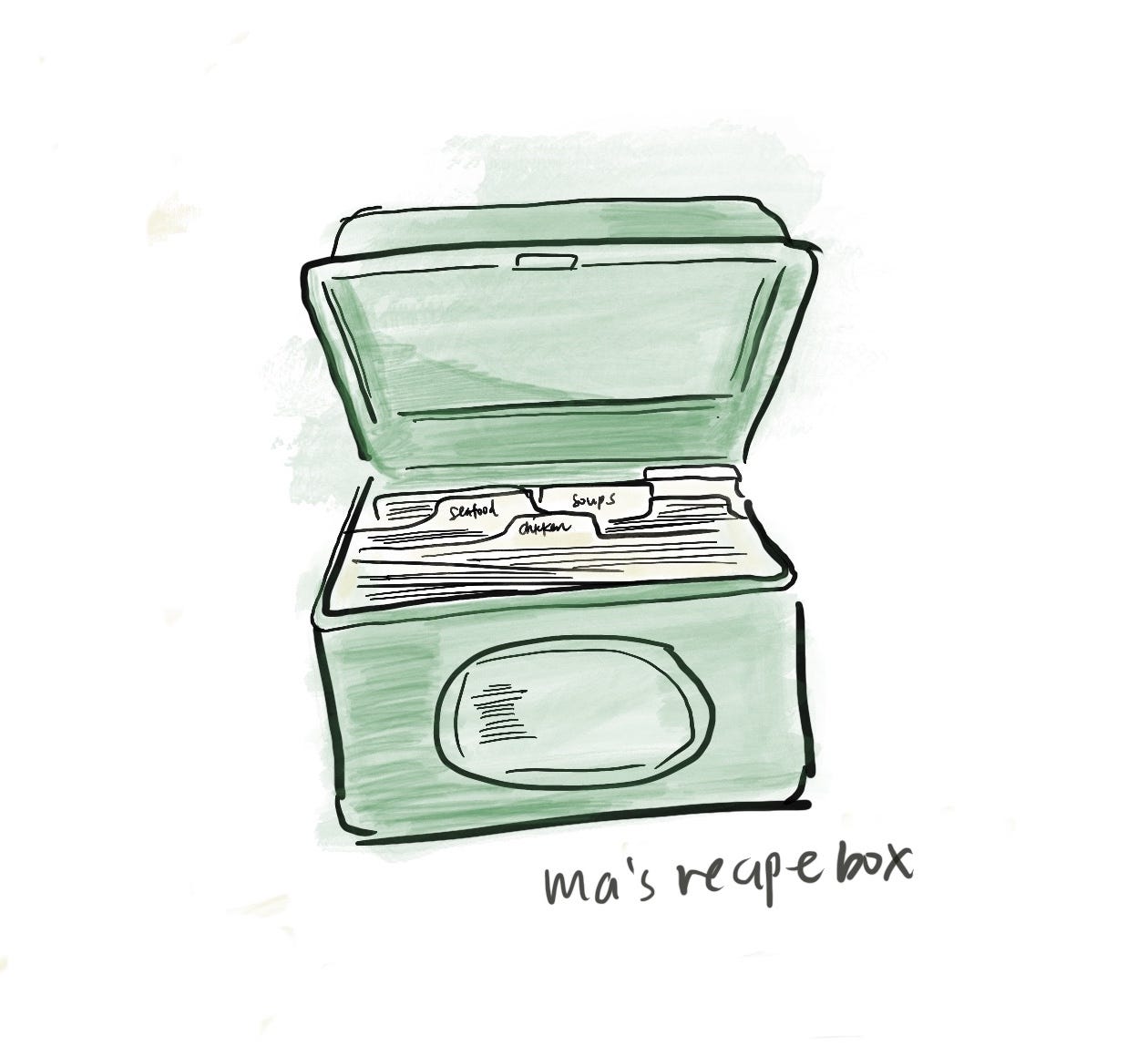

She would eventually learn other dishes, like menudo and mechado, from fellow Filipino immigrants. She would go to friends’ houses where they would go through how to cook a specific dish, step by step. I remember my mom’s plastic green recipe box filled with handwritten note cards listing measurements, ingredients, and instructions. She always kept it in the kitchen and brought it with her when we moved to the States. In 1997, we were living in San Diego, California, where there was a large community of Filipino immigrants with the supermarkets to match it.

Yet, even with a wider variety of ingredients available, I grew up eating meals that were mostly chicken, beef or pork-based. While fish was part of a typical everyday meal for my mom growing up, the only fish I could recall her ever buying was tilapia (anyone else think tilapia was Tagalog?) and bangus. Occasionally, my mom would buy crab when it was affordable. I recall trips home from Seafood City; I’d be sitting in the back of the van with chills down my spine, listening to the live crabs crawl on top of each other in the brown paper bag, ready to lift my feet off the ground if they were to get out. Sadly, that was the extent of my memories of seafood. When I asked my mom why we didn’t eat more fish, she said she never knew what fish to buy and frying was the only way she knew how to prepare it. I suppose she also thought we’d be too picky to even try other dishes, so why put herself through the burden of trying to find the ingredients and learning a new recipe?

My mom says she never thought to pass down Filipino culture through food. She wished she had that same joy she witnesses in others when they’re in the kitchen. My mom worked full time so she was out the door early in the morning; she only cooked so that we had food on the table. Looking back, I think those times she brought crab home was her way to bring a little bit of her past into the present moment with us.

Whenever I want to make a Filipino dish, I will often Facetime my mom. I’d ask her about ingredients, measurements and instructions. I can’t say her instructions are the most helpful. I’ve had to guess what “put a little bit, but not too much” translated to.

A common phrase I heard while making a new dish was, “just taste it.” The problem was that I felt like such a novice cook that even when I tasted it, I wasn’t confident what it needed more or less of. I would turn my camera towards the pot to show my mom if it looked right.

I remember my first attempt preparing kare kare: the meat wasn’t soft enough and no flavor came through. I begrudgingly ate it. Despite access to the internet and Facetime, cooking for me still consists of trial and error. I know I can quickly search up the recipe, but recipes online are another mom’s version of the recipe. I find myself wanting the dish to taste exactly how my mom made it. In a way, I may be asking, what flavors or tastes am I craving?

When I cook Filipino dishes, I find myself choosing dishes that bring comfort. One of my favorite meals to prepare is champorado; it’s comforting, sweet, and warm —everything I want when feeling homesick. Growing up, my mom would always leave a pot of food on the stove for us before heading out to work. It felt like hitting the jackpot when I would see champorado. She always found time to cook for us and meals like this connected us to her when she couldn’t be home. It signaled that my mom was taking care of us even when she was away.

Dishes like champorado, along with lugaw or sinigang, are my go-to dishes in my own kitchen. Hot dishes with rice make me feel closer to home, connected to my mom and my family. Rice makes me feel nourished and full. When I replicate these dishes, I pull my mom’s presence into my own kitchen, and I sit at the dinner table feeling held and taken care of. When I eat, it reminds me that all is well.

However, these are not regular occurrences. I only make Filipino dishes when I’m craving this taste or feeling. Every time I cook in the kitchen, I’m likely to use a recipe I pulled online or saved from one of my handful of cookbooks. Most of these dishes aren’t eaten with rice. It’s not that I don’t want to eat rice, we just have access to so many more options. Living in this current generation in the U.S. has really shown me the abundance of food I now have access to. I am one Google search away from a galaxy of recipes and cookbooks. I am less than fifteen minutes away from Filipino, Korean, Japanese, and Mexican supermarkets. Of course, let’s not forget how radically different the consumption of food has evolved. Take-out allows me to have a full meal within minutes, with restaurants and fast food chains on every block.

If food is a reflection of my identity, is it my responsibility to preserve Filipino culture through the dishes I make? What is my intention when sitting at the dinner table?

This past year has allowed me to slow down. I’ve gotten the chance to not only reflect on what food means to me, but also see ways I can be more intentional moving forward. The access to a variety of food has given me more options, and with these options, I have an opportunity to choose how it influences my Filipina American identity.

Preparing Filipino dishes will always be a way to cure homesickness and nostalgia. For me, it’s a chance to bring my past into the present. I am also seeing that it can be a way to bring my mom’s past into my present through my own exploration and preparation of the seafood and vegetable dishes she grew up eating. I hope to create similar memories with my future family. I know the actual food on the dinner table will be different from my mom’s —that’s inevitable. It has already evolved and morphed in my own upbringing. Now, I get to have influence in my kitchen and at the dinner table.

I don’t know how often I will be making Filipino dishes. I don’t know what kind of experiences or memories my future family will have when eating these dishes. What I do know is that the food at the dinner table and what’s prepared in the kitchen influences us in some way. It shapes experiences, memories, our identity. Can I cultivate these for my own future family? Can I honor this history and foster connection within my family and with our ancestors through white rice? One thing's certain: despite changing times, rice is a humble reminder of where my family came from. Because of this, rice will always have a place in my pantry, ready to be shared on my dinner table.

Credits

Kristine Angeles is a purpose & fulfillment coach based in Long Beach, California. She guides women in celebrating the connection between their own stories and identity. Connect with her on Instagram at @iam.kristineangeles

🗞️ Surprise, we’re printing a meryenda issue!

Yes, you heard it here first! We’re bringing “The Kape (ka-peh) Issue” into your hands! In celebration of Filipino-American history month and Philippine Coffee month this October, we are launching The Kape Project, a collaborative coffee box showcasing Filipinos in coffee. TAAS Collaborative is bringing together Filipino-American makers and doers @outofficecoffeeroasters + @wearesunraised + @readmeryenda to give you a meryenda experience: coffee, reading and stickers to rep our Filipino heritage. Pre-orders are now available for this limited supply box, which will include a special offering of Philippine specialty coffee from Benguet. Shipping available nationwide with some locations available for pick up.

What does it include?

☕️ Whole Bean Coffee - 3x bags (4oz each)

Out of Office Coffee in Long Beach, CA / Paul Barreto and Jonathan Ma — Benguet, Philippines

Kabisera in New York, NY / Augee Francisco — Kaulayaw Blend (South America and Africa)

Dear Globe Coffee in Baltimore, MD / LieAnne Navarro — Yirgacheffe, Ethiopia

🌞 We Are SunRaised - 1x sticker set

🗞 meryenda - 1x printed newsletter of “The Kape Issue”