Drinks, Among Other Things - Part II

The beverage issue is meant to highlight people who choose to refocus in these often vignetted spaces.

Magandang umaga! Welcome to part two of the beverage issue. Currently, I’m sitting in an airstream trailer at a small town at the base of the Topatopa Mountains on what’s supposed to be my mini holiday before I return to sterile hospital ventilation. But alas, here I am typing away, a glaringly large mélange of baked goods within immediate reach. It seems like I just can’t leave words to rest, even for a few short days.

I’ve just gotten off a morning chat with someone I met through an online group gozleme cooking session in which I met one of those individuals through an online chat on adobo (quite amazing this happened, really). The morning conversation brought a realization in my gradual shift in headspace over the year. I’ve noticed the same few words orbiting lately (is this the law of attraction working its magic?) — food apartheids, regenerative agriculture, sustainability, indigenous ecologies, labor chains, access and food security.

It got me thinking. The issues covered so far have mainly echoed my interests (and my comforts) — culinary history, anthropology, identity, personal stories. While we won’t be departing from those conversations any time soon (there’s still so much to be learned), I want to say how much I’m looking forward to navigating the ways in which food writing can connect this greater wealth of collective knowledge, especially since so many are already addressing and tackling these issues in this very space in their own ways. I tread with trepidation outside of my so-called comforts, but I’m excited to learn even more.

I do want to note that we’ll soon be introducing subscriptions. Yes, that does mean a sprinkling of issues will have a paywall, but in no way will it be hindering. Finding information surrounding Philippine food history is difficult enough so rest assured that none of the subscriber-only issues will lock that content (nor will it ever). Subscriptions will allow us to support writers, creators, and editors we hope to bring onboard. As we mentioned in one of our very first introductions, we acknowledge that our perspective is indeed limited as two Fil-Ams. How can we use this space to create even more diverse dialogues within our own narrative? I’m happy to say the next issue will feature our first guest writer. More on that later! — Jess

This beverage issue is meant to highlight people who, amidst all the anguish and chaos in today’s world, refocus in these often vignetted spaces. We don’t need to do extraordinary things to make change. There are people out there, every day, reimagining what is and what might be. If we choose to pay closer attention, we can find them everywhere, sometimes in spaces they had to make for themselves.

At the end of the day, beer, wine and cocktails are meant for enjoyment and are vehicles for connection. We can find joy in these beverages. We can also choose to elevate others in our choices when we consume these beverages; choosing one isn’t valuing one over the other. The emphasis on this Western narrative that everything must equal has cornered us into a lot of troubled thinking. Just like the many ways we choose to define ourselves, the choices we make aren’t a zero-sum game. When one rises, another can rise in conjunction.

Yes, I get it, not everyone craves the sociocultural fibers of what we consume. There’s a lot to reckon with what’s been done. Woven within these beverages are threads of oppression, colonialism, racism, classism and imperialism. I can’t help but question: how can we sew new threads over these bastions to create a fabric in which even the most minute fibrils are enriched in the larger tapestry? I hope these stories breathing among us give the reminder that we don’t always have to know how. Maybe what matters is that we do. A gentle nudge to keep going. Never lose sight of how far we’ve come. Never lose sight of what a thousand tiny threads can build, too.

Joel Darwin and Marla Darwin from Manila-based Palm Tree Abbey on community and asserting the Filipino palate.

Q: Tell us about Palm Tree Abbey’s story.

Marla: We are a Filipino company, but founded by two white guys, one half white guy. I feel like we still have to bring that into the mix. We're always going to be aware. The three guys come from a missionary background. You kind of want to [add] also how white guys who go to a third world country don't have the best of reputations. I don't want to hide that aspect of it, of us, either. We want to evolve that narrative.

Joel: We want to bring in a new perspective on how is this [brewery] very Filipino and yet what do we do to avoid becoming a gatekeeper or a Messiah figure that yells, “I am here to introduce craft beer.” There will always be people who want to be told what to drink and how to drink that. But our conversation is, “How can we come together?” Part of the vision that we have for Palm Tree Abbey — I say this because I'm representing my friends, John and Evan. Both of them are Canadian. John lives in Greece right now, in Lesbos, and helps out with an organization, an NGO, that helps refugees coming from Africa and now Afghanistan.

His whole vision for this is: can we turn this into a sustainable livelihood for refugees seeking help and get people to grow the ingredients there through a farm co-op and then start brewing beer because craft beer, apparently, in Greece is not that huge. It’s a shared vision that the three of us have — John, Evan and I. Then bringing creators together is hopefully going to take shape in us creating a space here.

What was the inspiration behind choosing to focus on Belgian style beers and sours?

Joel: My partners, John and Evan, really like Belgian beer. To me, to a certain extent, it's really some of the best beer in terms of just as a product. The trends here [in Manila] are very much what the trends were — in the US, when it comes to beer, maybe two or three years ago, everyone was like IPA, triple hopped, kind of craziness, which is great. That's not really my beer of choice. We like beers that are more rooted into tradition that have a craft and a history. So Belgians, you know, they've been brewing for centuries and we liked that component to the story.

The sours were kind of a gamble. Kettle souring as a method is something that a lot of bigger brewers are scared of just because of the risk of infection. If you use Brettanomyces yeast, you can really wreck a whole brewery. So it's the smaller kind of underdog, nano guys like us, that are scrappy enough to try it. That's kind of what I liked about it. And it just so happened to be the sour beers, especially the funkier ones that we can do, that work with certain Filipino foods really well.

Talk to us about the guyabano sour! How can Filipinos assert their voice in what they crave?

Marla: I never thought that guyabano would be a hype fruit. When [our guyabano sour] dropped, I had friends saying, “Zesto Guyabano was my favorite drink when I was a kid!” Apparently, people still have very passionate opinions about the flavors. They still yearn for that guyabano taste. Even Tang has a guyabano flavor. Suddenly all of these guyabano stans started messaging me all of their stories.

Even our customers themselves aren't aware of how much they love something until it's flashed before their eyes. You shouldn't disregard how powerful nostalgia is just because we don't talk about it. It's not something that's hyped or it doesn't appear in our ads. I feel like we're so dependent with tracking what's popular in the West or what's popular regionally that we tend to forget that we have our own hype fruits.

How did you choose flavor profiles to highlight in your beers?

Joel: It's a tricky thing with beer. Compounds and the yeasts that we still use are very much Western yeasts from Europe and the US. So we are kind of limited with what we can do with beer. But the goal is, can we, through the notes that most Filipinos would recognize - could that be the way they're now interested in fermentation and beer?

Marla: Some people ask, “Which of your beers tastes like Blue Moon or will it taste like this IPA that I've had?” Those are great beers, but we're not here to replicate things we've tasted abroad. Then you wouldn't be pushing the envelope. It will stifle us creatively and it's limiting.

We're already limited with our ingredients. I'm a big believer in brewing beer for Filipinos — for the Filipino palate. I want us to brew with [the mindset] of, “What are the flavors we yearn for?” That's what keeps us excited because there's a much bigger context around us.

When Joel was looking for guyabano purée, it wasn't that hard because before we even went into this beer adventure, our favorite people were farmers. We're really fascinated by people who grow things, who make things. I see ourselves as playing a role in that ecosystem.

You mentioned sourcing fruits from local farmers. Can you go into how that relationship has developed through Palm Tree Abbey?

Marla: We're just very lucky in that aspect because one of our best friends is the editor in chief of an agriculture magazine here. She has an initiative called Agripop, where she has her own community of young farmers. They've all inherited land but the typical sad story in the Philippines is a lot of people get the land, but then don’t want to farm. They want to move to the city, get a white collar job and they get sold off to the corporations. Then you have another plantation. But this community is trying to get more young people [and] tell them it's hard but it's a viable and rewarding business.

We've dipped in there by consuming their products. We’ve maintained friendships with them. The person who tried our guyabano sour — he and his wife have a farm. We did a farm tour. When it was time to look for ingredients, we already had the network. If we didn't know somebody who had guyabano, these people would.

We like staying friends with the farming community because they have so much indigenous knowledge. It's things that they pick up from other farmers and it's all oral tradition, all passed on. They naturally are able to talk about notes, complexities, even if they don't have a formal education, even if they didn't go to culinary school. They can really banter to you in their own vocabulary.

Joel: To add in, these are the guys that know of native fruits and flowers that aren't publicly available. There was this one talk we attended, the guy was going into what his family discovered, what they subsist on during World War II — all local grown fruits and flowers that are edible. It’s fascinating.

Can you talk about the design inspiration on the labels?

Marla: I guess the trickiest thing is our partners are way older than us. They're Gen X. We're millennials. I love these two guys, but I feel a cultural divide sometimes. But they're lovable! They're lovable bros. So even though I have all of these ideas, I didn't want to alienate them either. The design of St. Benedict — he was a big inspiration. The Trappist monk. I was looking at sketches, drawings, old stained glass art of Saint Benedict. John is in refugee work. Evan's wife runs an orphanage here in Manila.

Anything we do, it's with the hope and the dream that we could share benefits with other people.

I have this ideal version of life where you can derive a lot of fulfillment of cultivating a garden, making something with your own hands, distributing what you made to other people. Then you get it back and bring it back to the community. For me, that's what the monk symbolizes. The dream always is, how do we keep things sustainable, how do we rope more people in where you think of the bigger purpose. How do you find meaning? That’s the value that grounds all of us.

What are some of your favorite beer and Filipino food pairings?

Joel: The thing that I love about this country and our culture is we have our own category of food dedicated to drinking, which is pulutan. It's bar chow, but I feel like pulutan is really its own animal. In the minds of people going out for a night, with your barkada, you have to eat when you drink. It's not like hitting up a dive bar in Brooklyn and then getting a hot dog afterwards.

One friend of ours, she got the guyabano sour. It just so happened that her dinner was breakfast for dinner. Pork tocino on hot rice. Super greasy. Salty. Sweet. The guyabano sour cuts through it, balanced it. She told us about it and I was like, yes, that is awesome.

You think about pulutan, right? Super greasy and super salty. That actually came from the kind of beer that they were drinking, which was San Miguel. So Pilsner is a super light, crisp, clean tasting lager. It makes sense that’s how the food came about. Oily. Salty. Sour. I like a lot of sawsawan, when you're dipping into different kinds of sauces. These are combinations of soy sauce, vinegar, calamansi. And then for me, sili, like sili labuyo or chili.

Marla: Tell me the ingredients of your sawsawan and I'll tell you who you are.

Joel: Our Abby wit. It's a Belgian witbier. We call it a wit which is the traditional name of it, but the notes are basic. It's brewed with a high wheat malt bill, which has breadier notes. That breadiness works super well fried tilapia and the sawsawan with sili labuyo and calamansi. So our inspiration really is really pulutan food. That's one thing I feel more people [could try] — a wit or even an American wheat beer and fried tilapia with sawsawan — that would work really well.

Marla: Then think of your favorite Pinoy bar chow. We haven't even tried it with sisig. Sisig would be wonderful. And don't stop a traditional sisig. Try tofu sisig. Try bangus sisig.

Joel: We get a lot of ideas from the community. You just did a newsletter on kare kare, right? Kare kare is a great dish to talk about. Everyone has their own take on it. One of the guys here, he reviews beer pretty regularly. I was talking to him about sinigang na hipon. For me, a Saison really works well with that. It's dry. It's crisp. It's a good sour and dry kind of combo. But then he was like, bro, have you ever tried a Baltic porter or a porter with kare kare? First, I was like, I don't think I've had an Imperial or Baltic porter. I’ve had porters before, but the idea really intrigues me. I haven't tried it, yet. This is a recommendation from the community!

Marlo Gamora on the legacy of Filipino bartenders and reimagining the future for rum.

Q: Tell us how you found yourself immersed in the world of cocktails.

A friend of mine, Don, introduced me to Jeff Berry. At the time, I was into tiki cocktails because there was a really great bar here that I loved, Painkiller, in the lower East side of New York and I was like, I want to make these tropical cocktails.

So he introduced me to Jeff Berry. I picked up his book, Sippin’ Safari. I opened it and the entire book was based on Filipino bartenders. It just blew my mind. As for cocktail making — just the escapism that it provided at the time. I delved deeper and found out that a lot of the drinks that we’re drinking were made by Filipinos during this whole tiki renaissance. My love for rum just grew and grew.

I started geeking out about rums and geeking about cocktails and how to make cocktails with rum. It was all within that cocktail and bartending umbrella where I learned about Filipino bartenders and rum.

Did bartending help you navigate your Filipino identity?

Growing up, I always found myself being the only Filipino in the room. I rode a motorcycle and a lot of the guys I rode with and hung out with were white dudes. I was into vintage culture as well. I love male fashion, being a Sartorialist, dressing up as a gentleman. I had Filipino friends, but I wasn’t into exactly what they were into.

In bartending, there was only a handful of other Filipinos that I met. And actually, the [Filipino] that I met — he’s one of my mentors. He got me to where I'm at today. When bartending came along, I met Tomas de los Reyes. When I first met him, he was actually opening Jeepney and they said that they were looking for a head bartender. At the time I was already geeking out about cocktails, geeking out about tiki culture. I came [to Jeepney] and it was just so familiar. It was like going to my family friend's home and having all the Filipino food and jamming out to all nineties hip hop and I was just surrounded by Filipinos. So I took the job there. Well, it was funny, while I was getting into that job, I was already doing research as far as Filipino bartenders.

It just blew my mind that there was this underground — not underground, but subtexts — where Filipino bartenders, and their influence weren't mentioned when these cocktails were coming out.

Since that point, after reading the book and seeing other Filipino bartenders and meeting Filipinos in hospitality, I was like, okay, now this is where I felt very proud of who I am as a Filipino and proud of who I am as a bartender and what I do.

Okay, heavier question here. How do you navigate being Filipino in tiki culture, where the beginnings are built on cultural appropriation? How are you reimagining tiki culture and how do you think it can move towards a better future?

I think about it all the time. I like the tiki community and the folks are wonderful people. I know that they're always coming from a good place. Being a Filipino - it's been one of those things where I jump back and forth, you know, where I'm conflicted on cultural appropriation. I'm navigating through rough waters, just going between both sides. I feel like the conversation is changing and it should change.

When it comes to the revival of tiki culture and where it came from, it was the 1930s — they created a space. They created escapism. Part of it was created from truth. Part of it was not. Obviously they hired Filipinos because we’re from the Pacific islands and they were trying to create an atmosphere. But that was the 1930s and nowadays a lot of people are changing and America is changing and the temperature of culture is changing.

Some places and events are actually raising money to give back to these islands and these cultures. I think it's great. If everything's being pushed in a positive sense and in a very understanding sense and people are open to the conversation - just keep it going and let it grow.

Try to take it from other people's perspective and say yeah, you know, there’s a lot I still need to learn. But let's also enjoy this time. Let's go enjoy this Painkiller or this Missionary Downfall. People want to be taken away and if tiki can do that, can make them happy — let’s do it.

To be honest, I was unaware of how much Filipinos influenced tiki culture. Can you expand on what pieces within that history stood out to you?

When I was reading Sippin Safari, there was this mecca of a bar in California called Tiki Ti. I don't know if you've been yet, but it’s actually family owned and it was one of the first known popular tiki bars. It’s one of the meccas to go to if you’re a tiki geek. It was actually opened by Ray Buhen and Ray Buhen is Filipino. He was actually one of the “Four Boys” at Don the Beachcomber.

When tiki first started, he was one of the first bartenders there and the first bartender to open up his own place. His son still runs it. Mike Buhen is still there and just reading that a Filipino could do that was just a big inspiration for me.

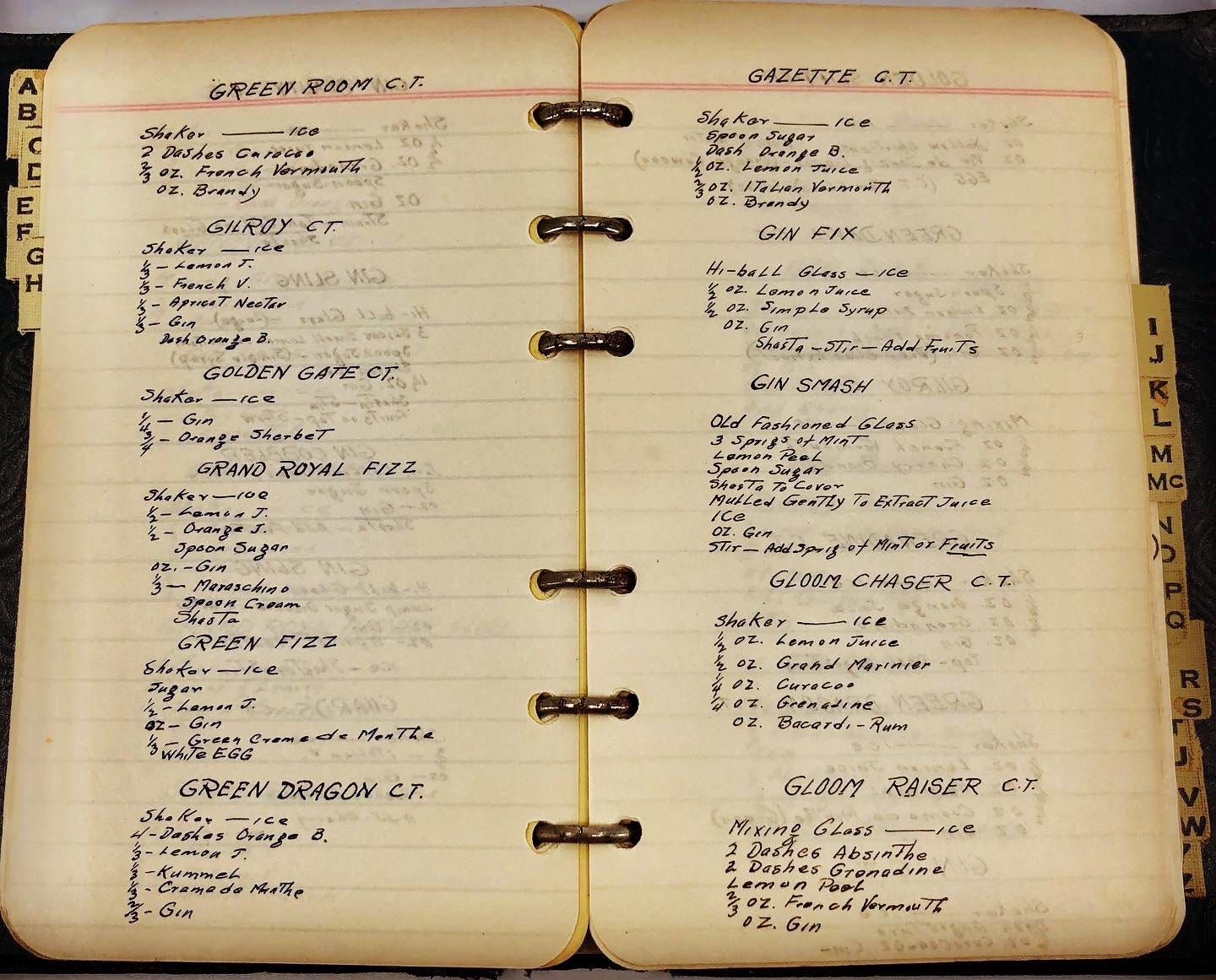

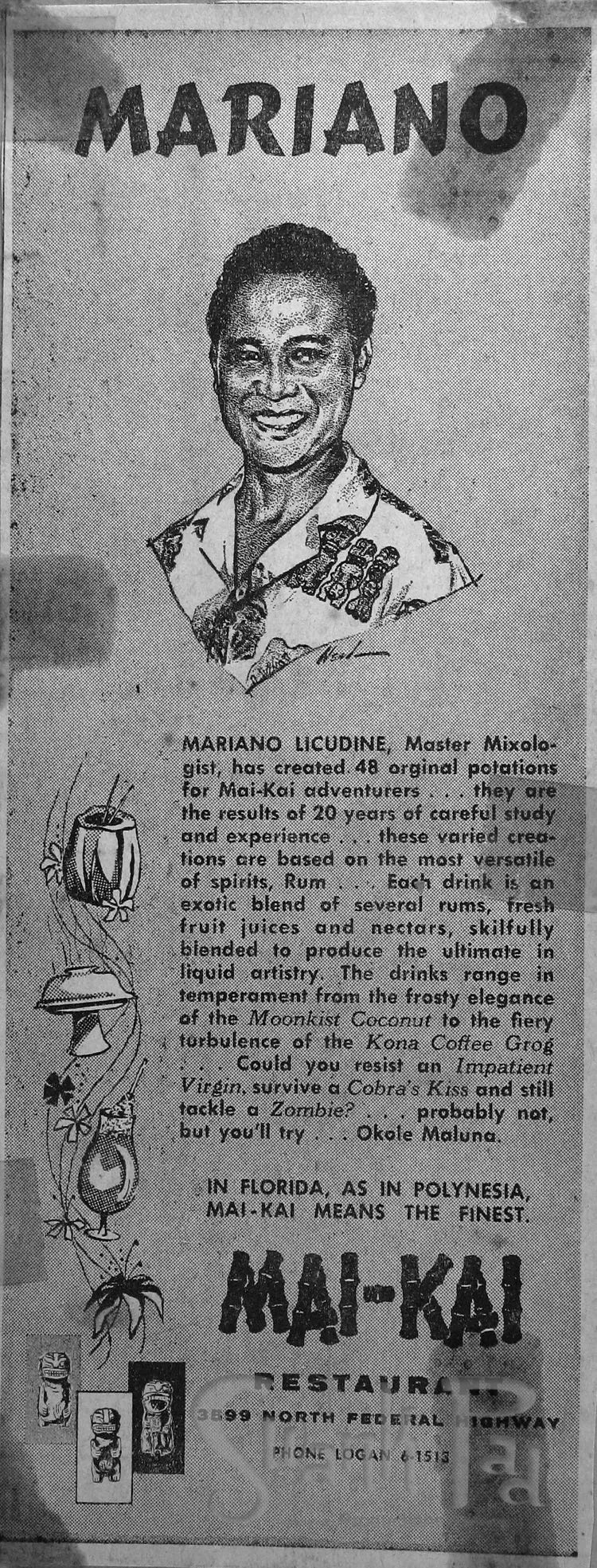

The book also goes on to talk about Licudine, Dick Moano, Dick Santiago. There are so many other Filipino bartenders that came from Don the Beachcomber and some from Trader Vic and then moved on to open up their own places and consult. They kept their recipes very private. If you wanted the cocktails, you had to hire the bartender who happened to also be Filipino and they were pretty much all over the country. Tiki bars were popping up left and right.

There were variations on the cocktails that they actually made. Obviously they helped with a lot of the development of a lot of the cocktails, but Trader Vic and Don the Beachcomber said it was their cocktails because it was their restaurants. But, I'd like to say that a lot of the Filipinos working behind those bars were the ones that were actually coming up with these cocktails and that they're the ones who introduced different kinds of juices and syrups, and then just mixed about and created these cocktails.

As someone who has been in the industry, how has rum consumption evolved and what are your thoughts on the future of rum?

Rum has been one of those spirits that has been misunderstood. You have the tiki boom from the 1930s to the late 60s. All of the cocktails were made with rum. Since then, ingredients got cheaper. Cocktails got sweeter. From the 70s to about the early 90s was the dark era of tiki culture. People's mindsets changed from the dark ages of tiki when rum was sweet. You associate rum being very sweet or in a sweet drink because it's made from sugarcane. Spirits are actually made from different kinds of sugars. It's just rum that is made from sugarcane and that's why a lot of folks think it's very, very sweet.

I'd like to say in the 90s and 2000s until now, there's been a nice growth of rum being drier. Different styles and expressions of rum are coming out. I'd like to say that there's this nice premiumization of rums coming out. You can sip on a very well aged rum from Venezuela or from Barbados or Africa. There are rums coming out from Africa. Everywhere sugarcane can grow or where you can get sugarcane they're making rum. Everything has its own terroir and flavor profile. And the way it's made. It's pretty exciting to see that.

Amongst us Filipino bartenders we're always using rum. We're always playing with rum. It's been ingrained into the cocktails we've been making. Seeing a bunch of other rum brands come out and especially Filipino brands come out and representing rum and Filipino culture in that way — it's really great to see.

I'd like to say palates are getting drier amongst folks who drink [rum] in general. There are some that like the sweeter drink still and that's why you have rums that add sugar into it. There's definitely something for everyone, but I'd like to say that the palate has been changing to a bit drier, especially for a lot of rum producers.

Nowadays, most folks should be educating themselves about the rums and where they're coming from and how it's being produced. There's been a big topic amongst the rum forums about the colonization of a lot of these islands and how they took advantage of the community and the country that it took from. There's a lot of big discussion about where and how and when and why rum is produced. Just read up on what's been going on in different islands, especially those that have such great cultural history but have been influenced by these colonizers. It's becoming a growing conversation because sugarcane was a commodity. Rum is a commodity and a lot of colonizers took advantage of that — pretty much just reaped all the rewards without giving back to where they're actually getting it from.

Special salamat to:

Credits

Maysie Lecciones is a multidisciplinary designer utilising her diverse areas of expertise to create thoughtful, successful designs. She actively uses her design skills as an active member of The Entree.Pinays, a group of women based in Melbourne who advocates for Filipino food, arts, and culture in Australia. Find more of Maysie’s work on her website or her Instagram.

Current meryenda

Without Filipino Bartenders, There Is No Tiki | PUNCH by Drew Lazor