Sinigang is a Verb

How regionality and sinigang come together in Filipino/x America. Words by Jeremy Balagey, photos by Eugene Kim, illustration by Cassandra Balbas

Hello, and welcome to another meryenda Monday. Currently, meryenda is a reader-supported independent publication. If you find value in our work or use it as an educational resource, consider becoming a paid subscriber for $5/mo or $48/year. If you’d rather make a one time donation, please reply to us directly so we can work something out. Your contribution allows us to nurture this space such as commission works from our community. Salamat 🫶

It’s our final issue for 2022! It’s the end of 2022? I can hardly believe it. It seems just like yesterday I announced I moved indefinitely to Manila. Here I am, eight months down the road and I am still finding more thoughts to figure out and revisit more than ever. The year 2022 has been a very reflective and personal one here on meryenda, with admittedly not much public engagement. We are am aiming to shift that in 2023.

While my focus has been a translation of experiences here in the Philippines, I wanted to circle back and finish the year with a feature on diaspora writing. Jeremy Balagey is currently studying Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University and has been interning with meryenda the past four months. He brings his learnings from academia and invites us to examine Filipino food regionality within the US. The topic of his senior thesis will be food media discourse and its potential role in shaping perceptions of Filipino American cuisine. This issue is meant to begin unraveling that question. We hope you enjoy and eat many nourishing bowls of sinigang afterwards.

To those who have been with us since our first issue published on ube origins as well as to the many new faces who have joined since, maraming salamat. meryenda isn’t possible without your support and continued interest in learning more about Philippine culture and food ways. We’re still figuring things out as we go, how to connect, how to pursue not a perfect story, but a story. Our stories. Telling them will always be a work in progress. We’re just incredibly thrilled and grateful you’re along with us on this ride.

Stay hungry and stay curious,

Jess + Cassandra

Sinigang is a Verb

Like many who have moved away from their childhood homes, I long for my mother’s cooking.

In my first few years away from Stockton, my hometown located in the northern part of California’s Central Valley, I would try to emulate her recipes from memory, namely chicken adobo, pork barbeque, and tinola. My cooking trials were decidedly unexceptional, edible but superficial in flavor and lacking what Corina Zappia refers to as “tancha”, an inherent knowledge of how to harmonize the flavors in a dish.

It wasn’t until the last few years, though, that I thought to consult my mom’s recipe book.

It lives in a kitchen drawer located below another housing packets of Chinese hot mustard, soy sauce, ketchup, and McDonald’s Sweet ‘N Sour; to the right of a cupboard filled with mountains of tupperware and reusable water bottles; to the left of an oven used solely to harbor pots of still-good-to-use cooking oil. It’s vivid pink with red binding, Hello Kitty emblazoned on the cover.

The recipes span years and generations, from the early nineties to the mid 2000s, from my great-grandmother to my grandmother and great aunts, all recorded in my mother’s familiar abstruse handwriting. Dog-eared, furrowed, and sticky in spots like a well-loved one should be, the recipe book contained the small details missing in my previous attempts at cooking family recipes. Noticeably absent is sinigang, a staple in my mom’s repertoire.

I asked my mom for her sinigang recipe. Her answer surprised me: it was less a list of quantities and cook times and more a game of Tetris, decidedly unscripted, shifting to fit time and budget constraints and ingredient availability. She used to prefer Knorr sinigang mix as the broth base, but she’s noticed the flavor change over the years; now, she chooses Mama Sita’s for its superior sour-to-salt ratio and rounder flavor. Yellow onions and ripe Roma tomatoes were ideal to develop the broth’s flavor, but white onions would do if they were cheaper and less ripe tomatoes should be sauteed in order to extract a robust sweetness. Sinigang na baboy (pork sinigang) was the most requested iteration by my dad and sisters, so my mom would seek out fatty pork ribs for their combination of fat, meat, and collagen that would gelatinize the broth. If unavailable from our local butcher or supermarket, bone-in pork belly (liempo) achieved the same effect. When I was younger, she would use chicken when we couldn’t afford pork or beef. Kangkong, okra, and Chinese long beans provided balance to the unctuous braised pork, but plenty of spinach, mustard greens, and even broccoli filled in admirably. In these ways, sinigang to my mother is more of a verb than a noun.

Of the soup, Doreen Fernandez writes, “[Sinigang] is adaptable to all tastes (if you don't like shrimp, then bangus, or pork), to all classes and budgets (even ayungin, in humble little piles, find their way into the pot), to seasons and availability (walang talong, mahal ang gabi? Kangkong na lang!).” Just as one can adobo anything, to sinigang represents a way to sour that which is available and plentiful.

This is not to say that fresh and local produce alone comprise a definition of regionality. J.M. Valiente-Neighbours finds multiple definitions of “local” food in a 2012 study of Filipino immigrants. Among them is immigrant identity-based local food. Valiente-Neighbors writes:

This immigrant identity-based localism is inward-looking to both the body and the mind; it is lived daily in immigrant Filipino food practices: shopping at Seafood City (grocery stores that target Filipinos), tending the garden with familiar vegetables and fruits, and the preparation and cooking of Filipino dishes.

Valiente-Neighbours describes a practice of holistic regionality prompting reminders of homeland. Not only comprised of eating Filipino food, it encompasses daily exercises of grocery shopping and backyard farming. My grandmother, Erlinda, subscribed to an immigrant identity-based local food. Part of the allure of packaged sinigang mix is its remarkable convenience that somehow makes it more delicious—accessing flavors of homeland in the time it takes to boil a pot of water. Tamarind paste was harder to come by and much more labor intensive than using packets of mix. She prepared oceans of sinigang for her farmer’s market food stall and separating seeds from tamarind pulp would have been arduous work for her and her only regular helper. Sinigang mix helped to feed her customers and nourish her relationship with homeland.

Vanjo Merano of the food blog Panlasang Pinoy also attests to the convenience of sinigang mix, but mentions the widespread usage of non-tamarind souring agents in the Philippines, such as guava, green tomato, green mango, pineapple, katmon, and kamias. Abi Balingit of the food blog Dusky Kitchen also values the convenience of sinigang mix, which she keeps in her pantry alongside other shelf-stable Filipino staples like ube jam, various vinegars, and banana ketchup.

While she utilizes local ingredients where she can, emulating traditional Filipino flavors is also a priority when cooking, which sometimes entails making use of what’s available. When working on her upcoming cookbook, Mayumu: Filipino American Desserts Remixed, she found local calamansi, the intensely flavored citrus ubiquitous in Filipino cuisine, difficult to procure.

“I definitely struggle to find any calamansi, so I would resort to frozen calamansi packets. It’s kind of like pick-and-choose your battles with certain things you’re trying to make. I will bend over backwards to find a calamansi farm in [New] Jersey, but it just takes so long that by the time I need it, it’s too late. Then, I’ll just use lime and orange and mix the citruses together.”

Contemporary considerations also shape an ever-broad expanse of regionality. Filipino vegan food has become increasingly popular, concurrent with consumers eating less meat and considering the impacts of food systems on climate change. In the Bay Area, the pioneering food truck Señor Sisig launched an all-vegan truck, Señor Sisig Vegano, in late 2020. Reina Montenegro helmed Nick’s Kitchen, the first vegan Filipino brick-and-mortar in the San Francisco Peninsula, for years until pivoting to open her eponymous restaurant, Chef Reina, in 2021.

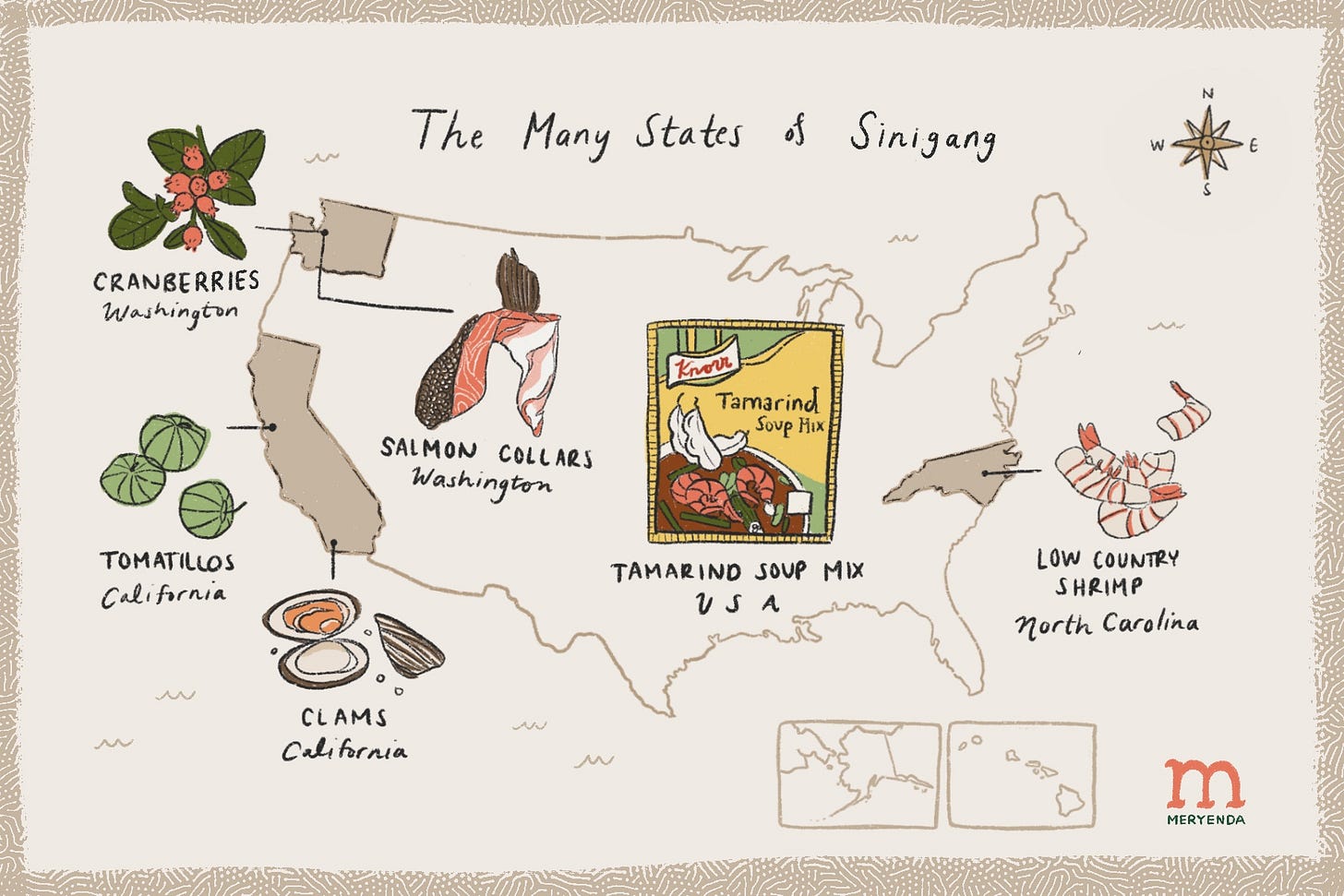

Other chefs prioritize the use of local ingredients in renditions of Filipino dishes in their iterations of regionality. In Seattle, Washington, Aaron Verzosa of Archipelago engages the bounty of the Pacific Northwest, having used Oregon cranberries and rhubarb to sour sinigang and salmon for house-made bagoongs. At Oriental Mart in Pike Place Market, Leila Rosas famously uses salmon collars in place of the traditional bangus in her sinigang. Tara Monsod of Animae in San Diego made a sinigang with clams as the chef-guest of an event produced by the Filipino Food Movement, a nonprofit that “preserves, promotes, and progresses Filipino cuisine”. And across the country in Asheville, North Carolina, Silver Iocovozzi has utilized lowcountry shrimp in sinigang at their restaurant Neng Jr.’s.

In the past week, I tasked myself with making sinigang with ingredients from my local farmer’s market, applying the lessons learned from my mom’s recipe. Instead of packaged sinigang mix or tamarind paste, I was able to sour my broth with tomatillos, a staple in Mexican cuisine favored for its bright acidity and vegetal notes, an unexpected find in early December. While we enjoyed an extended tomato season here in the Bay Area, they were unavailable during my market trip. I thought without tomato, the broth may stray too far off course, but I recalibrated and allowed the market to reshape my sinigang. As a replacement, I took a cue from Tom Cunanan, chef of Pogiboy in Washington, D.C. and Soy Pinoy in Houston, and fortified my broth with dried shiitakes, which share a similar ability to deepen the broth’s flavor. While I made sure to buy quality pork (I picked up St. Louis-style ribs and belly), the vegetables in sinigang were always the most special to me, so I loaded up on spinach, turnip and collard greens, along with Tokyo turnips and daikon. This particular sinigang serves as a salve to the nipping cold front sweeping through the Bay Area and a way to center local produce and lessen my reliance on imported tamarind.

Each time I riff on sinigang by replacing tamarind or swapping vegetables, I’m reminded of the first time I did so. It was purely tumultuous and I thought the entire time cooking, “What am I making? Is this actually sinigang?” There weren't enough vegetables, my pork was tough, and, most conspicuously, the color of the broth didn’t satisfy the ambered translucence of packaged sinigang mix. It most definitely wasn’t my mother’s, but, as Martin Manalansan writes, “This is the messy reality of any cuisine, whether it is called fusion, diffusion, or confusion”.

Regionality is just so, eschewing a strict definition, receptive to ideas of homeland and locale, delicious all the way through.

Credits

Jeremy Balagey is a a cook and undergraduate student at San Francisco State studying Asian American Studies. He is proudly from Stockton, CA and moved to San Francisco in 2012. In that time, he has worked as a barista, line cook, and pastry chef. He is interested in all things food— especially the intersections of food, identity, and politics, the representation of Filipino food in food media, and the politics of tipping in restaurants. Get connected by replying to this email.

The Most Popular Essays of 2022 👀

The Last Vestiges of Philippine Sea Salt

One day, Philippine salt can silently fade into another cultural artifact. We’ve lived without Philippine salt all this time so why care now when finely ground salt is conveniently within our reach?

How About Wine from the Philippines?

While most of wine literature and research focus on grape culture, several studies have been conducted to assess the potential of fruit wine. There have been promising results from many fruits familiar in the Philippines: mango, lychee, bignay or bugnay, guava, passion fruit, and rambutan. This leads back to the question that has fired every neuron of my culinary cortex since visiting the province: why don’t we know more about Philippine fruit wine?

Fizz, Funk, and Flavor: Following Philippine Ferments

That’s not to say the practice of fermentation is fraught. This generation, fueled by curiosity and growing food conscientiousness, is revitalizing this seemingly mystified practice. Fermentation has never been more exciting and in a time that urges humankind to rekindle care and sensibility for the world around them, fermentation has never been more relevant.