Is it me or is our connection to Mexico such an overlooked portion of our history? Trade between Philippines and Mexico (of course under the watchful Spanish eye) existed for 250 years. While you let that marinate, I want to announce: we are looking for more bites of meryenda. You can find submission details at the bottom of the newsletter (yes, there’s more beyond the comment button, but please, we also ask that you make use of the comment button 🤓). With that said, we hope you enjoy this Monday’s issue.

Perhaps one of the most interesting yet lesser known influential gastronomic exchanges that transformed Filipino cuisine is the one between the Philippines and Mexico. Spanning 250 years between 1565-1815, the Manila Galleon Trade was the world’s first recorded global trade route, shuttling luxuries of Asia (Old World) between treasures of the Americas (New World).

The ships, called Manila galleons, were among the most flourishing of their time. While Manila was the primary terminal for a majority of the trade, the first ships sailed from Cebu, where commander of the Spanish fleet, Miguel Lopéz de Legazpi, docked on his voyage from Acapulco, establishing the first Spanish settlement on the islands. The return navigation was entrusted to an Augustinian sailor, Friar Andrés de Urdaneta.

On June 1, 1565, the flagship of the Spanish fleet, the San Pedro, sailed from Mandawi Island in Mactan, Cebu across the Pacific to the Americas. The voyage spanned an exhausting four months. Urdaneta was pivotal in discovering the return voyage to Acapulco, New Spain (now Mexico) and the successful trek set in motion centuries of trade between the Philippines and Mexico.

Cebu ceased as the main port when the Spaniards moved the capital to Manila in 1571 to serve as Spain’s major trading hub in East Asia. The Galleon Trade soon transformed Manila into a city of dreams, becoming a mecca of trade promising wealth and prestige. The capital attracted royalty, foreigners, and locals alike to plunge into the gamble of possible riches. This influx of people, goods, and ideas would alter Philippine circuitry and redefine culture, traditions, language, and cuisine. By focusing on the exchange of influences during the Galleon Trade, we can also explore how Filipino tastes and preferences were shaped during this era.

—

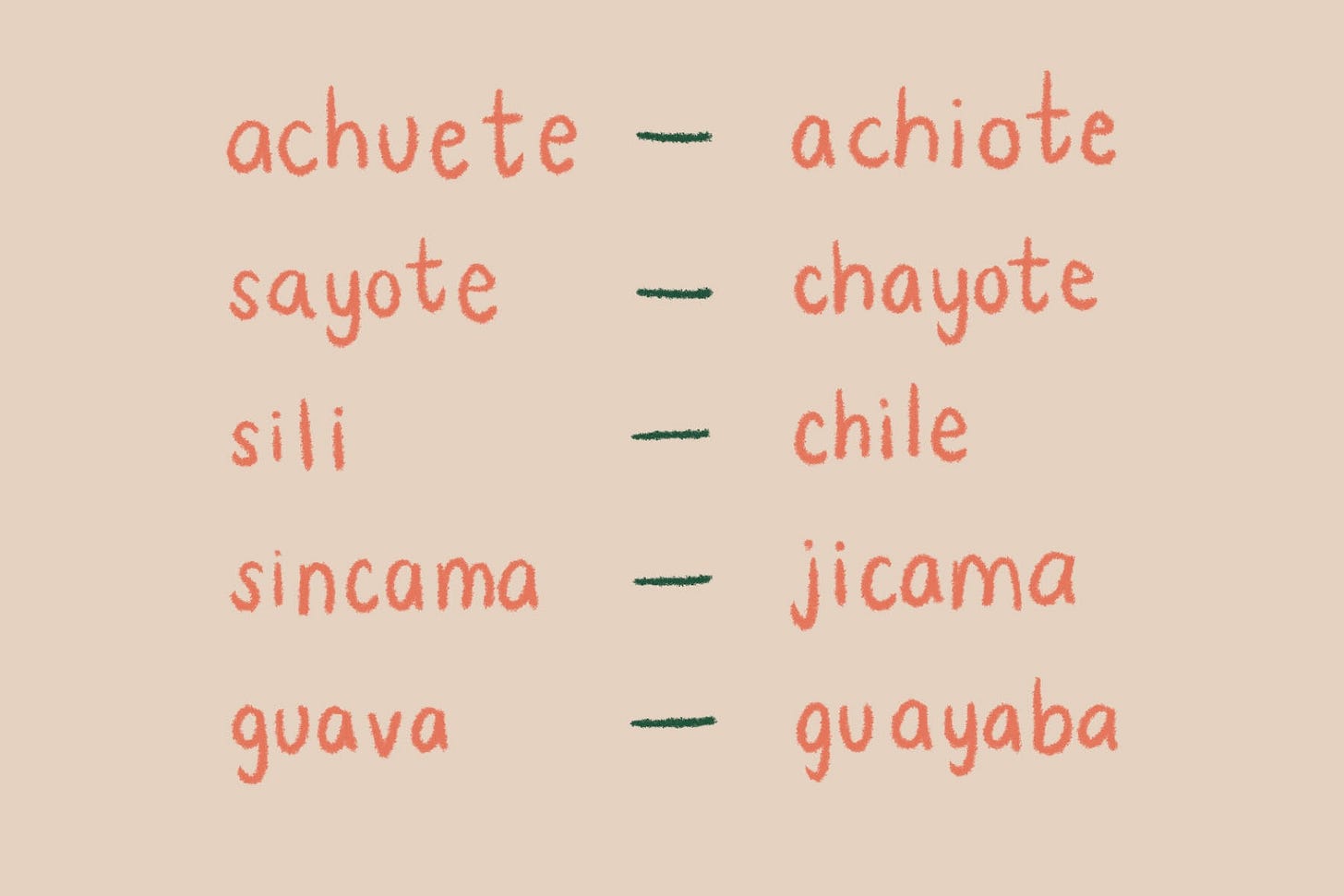

The global exchange between the Old World and New brought profound gastronomic changes. Food from Mexico became injected into Filipino culinary life — tomato, pineapple, singkamas, avocado, atis, peanuts, and kalabasa — to name a few. Rafael Bernal, a Mexican diplomat and novelist, studies the adaptation of Mexican ingredients into local lexicon in his book, México en Filipinas: estudio de una transculturación (1965). In it, he provides a glossary examining Mexican origins in Philippine foods, some of which are highlighted below.

Doreen Gamboa Fernandez, a culinary historian and writer whose extensive works on Filipino cuisine have resurfaced into the spotlight, dedicates an entire chapter in Tikim on Philippine foods that reveal Mexican origins, noting they “are especially engraved in the language.” Fernandez explores the uses in both Mexico and the Philippines as well as gradual diffusion in Philippine cuisine.

In describing sayote,

“The Mexican chayote grown abundantly in the Philippines, and is made into pickles and cooked as a vegetable, generally guisado, in lumpia or as pickles. It also became the substitute in apple pies when apples became scarce and expensive.”

When searching for pineapple origins, Fernandez digs deeply into historical records to analyze the evolution (or lack thereof) of vernacular, explaining,

“The fact that it is called piña/pinya in almost all Philippine languages… suggests that it came to the Philippines from Mexico, not China.”

She explores not only ingredients, but dishes. In comparing methods of preparation in the two countries, specifically in champorado, she brings up,

“... in the Philippines, it is a breakfast dish of rice cooked in chocolate and milk (sometimes coconut milk). It is often eaten with something salty, like dried salted fish or dried salted venison. Corn in Mexico, rice in the Philippines; only the sugar is common.”

As she does in the entirety of her work, Fernandez approaches outside influence without embellishment, documenting much more in a way a researcher does: objectively and critically. Rather than praise Mexico’s influence, she instead probes the question of: how was Filipino food before and after the Galleon Trade? By presenting the transformation of culture in detailed recording, she creates an architecture for the present and future to reflect and build upon. We can see our taste for spice and richness develop. There are some surprises: fruits we associate as being native to the Philippines — pineapple, papaya, and atis (custard apple) — came through the corridor of Mexico. In her attempt to understand Mexican presence in Philippine culture, Fernandez reflects,

“The Mexican connection remains — in the kitchen, in the palate, in the heart — a brotherhood beneath the skin, deep because it voyaged through history into society and life ways, and then became entrenched in the culture.”

The lasting legacy of the Galleon Trade and our Mexican connection persists today. We can see it with the use of guava and pineapple as souring agents in sinigang. Kapampangans make a local version of tamales (both singular and plural are referred to as tamales) or bobotu, using the region’s abundance of banana leaves in place of corn husks and rice flour in place of masa.

Descendants from the waves of Filipino migration to Mexico are found particularly in the cities of Colima and Guerrero, where Philippine influence remains palpable in local food culture. In Colima, tatemado is a dish of stewed pork in coconut vinegar. Tuba, a coconut wine in the Philippines, is served as tuba fresca in Colima, a popular beverage made from coconut palm sap often topped with a sprinkle of peanuts. There are also theories that mezcal and tequila production evolved from coconut distillation techniques brought by Filipinos during the Galleon Trade.

As the diaspora finds more interest in their histories, one may ask, is it necessary to continue to have conversations surrounding the influence brought as a result of colonial conquest? How do we navigate the impact of one culture on another and how do we do so without tarnishing Filipino food’s rich history?

The Manila Galleon Trade would emphasize a phenomenon known as transculturation, a term first coined in 1940 by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz. He uses the term to describe the transformative processes that unfold within a culture and I believe it to be applicable when trying to answer those questions. He writes,

“... the word transculturation better expresses the different phases of the process of transition from one culture to another because this does not consist merely in acquiring another culture, which is what the English word acculturation really implies, but the process also necessarily involves the loss or uprooting of a previous culture, which could be defined as a deculturation. In addition it carries the idea of the consequent creation of new cultural phenomena, which could be called neoculturation.”

I bring up transculturation in an attempt to understand the breadth not only of the Philippine-Mexico cultural exchange, but also of the many outside influences that have shaped Philippine cuisine. Navigating transculturation through the exchange of food is just one aspect in its relation to the extremely complex issues interwoven within its definition - its birth as a result of colonial conquest being one of them. In fact, I think exploring the phenomena of transculturation unbinds us from our limited views of understanding our culture and our way of viewing the world.

By traversing Philippine cuisine through specificities — as an exploration of islands or through processes of adoption and imposition — we can begin to probe beyond the paradigm of Filipino food simply as a coexistence of cultures. I’m not saying being a cultural melting pot is a negative thing; some of my favorite dishes are a result of cultural intermeshing: caldereta, champorado, lumpia, and pancit. However, we lose by locking Philippine cuisine into an oversimplified definition rather than giving ourselves the chance to explore the richness pushed in its periphery; we sacrifice complexity for convenience.

Food, like culture, is dynamic. It evolves. It adapts. It is sometimes eroded and erased by dominant world views, but it is up to us to learn and expand our understanding. Countless others have faced similar questions, preserving culture and tackling the question of identity through many forms of expression: as chefs, farmers, singers, artists, dancers, advocates, teachers and industry leaders. It is when we find coherence within ourselves through our own individual interpretations that we can build and enter a bigger web of understanding, allowing our culture and food systems not just to survive, but to grow and succeed.

The Philippines is an archipelago of over 7000 islands with a diaspora spanning the globe. We may be unaware of it, but the discussions occurring within our own networks are weaving us closer together. I rejoice knowing I am hearing the faint sounds of a concert of interconnectedness, each one of us playing the instrument we are most attuned to. I believe Belgian physical chemist, Ilya Priogrin, explains this most beautifully and it is a quote I will leave to you to ponder:

“When a system is far from equilibrium, small islands of coherence in a sea of chaos have the capacity to lift the entire system to a higher order.”

Discourse with the Diaspora: Thoughts on outside influence in Filipino food conversations

With Alexis Convento (she/her):

Filipinos are so mixed between Chinese influence, Spanish and American colonization, Muslim culture. There’s a lot happening and that’s the cool part about being Filipino, having all these different points to come into our cuisine, or, our culture to begin with.

How I’m unlearning these histories, at first, is how far back can I go in my food, to imagine, this dish without any influence of colonization?

I think [outside influence] is also such a part of our histories, it’s not necessarily, ridding of that or shedding of that — which I think sometimes it’s valid — but in terms of now, in terms of a decolonization practice for me, is accepting that these are part of our histories and that painful part can be turned into a protest in ways... acknowledge the history, but play with the history to allow something new to form.

With AC Boral (he/him):

To begin the discourse within our communities, I think it is important to make it kind of like a cookie cutter history lesson… that’s where it should begin. We cannot talk about our food culture and food history responsibly without talking about colonial history.

A big reason I’m drawn to the Galleon Trade is because it’s a big part of lost history. It’s something that, when you dig deeper, it’s interesting to think that we may have a lot more Latino blood in us and vice versa. There has been the exchange of people… it’s something that’s intriguing, because, well, I can’t pinpoint it, but… let me break it down in some ways I can: I grew up alongside a lot of Mexicans. Also, I never identified as Mexican, but I guess you can sort of say I envied that Brown confidence in their identities. I think that’s why I’ve stuck around: because it’s a close analogue to my influences in food and my approach to food.

Credits

Filipino food graphic provided by Jake Gavino, a Bay Area based graphic designer with a penchant for illustration. He is currently designing for globally known clients at Turner Duckworth. Jake received his B.A. in Studio Art at UC Irvine and his MFA in Graphic Design from CSU Long Beach. Find more of his work on his website and his Instagram.

In Case You Missed It

Where Does Ube Really Come From?

Current meryenda

Reading Dinuguan by Any Other Name (Is Still Diniguan) by Yasmin Tayag and munching on ube hopia from Luisa & Son Bakery 🍠

Submission Calls

Want to dish out some meryenda? We created this platform because we believe more spaces like this need to exist — a place where we can unapologetically cover Philippine culture and cuisine. As a budding project, we want to be transparent: at this time, we unfortunately cannot provide monetary compensation. The time and effort we pour into this space emerges purely from the desire to better connect with our roots and challenge current food media discourse. If this work interests you and you’d like to pitch to meryenda, please send writing or illustrative ideas to: meryendamail@gmail.com

This is such a great newsletter! Please keep writing. Look forward to reading more of your stuff!

Something else very interesting about pineapple is that its fibers are used to create a very fine cloth, called piña cloth, in the Philippines. As a result of the Spanish invasions of the Americas, and then later the galleon trade, pineapple was cultivated in the Philippines and this textile tradition developed. Piña cloth was even exported from the Philippines to Europe. I'm not a historian of this particular textile or textile tradition, but it's fascinating and worthy of more study!