Keeping the Culture(s) Alive

Speaking with a Filipino community connecting with the practice of fermentation

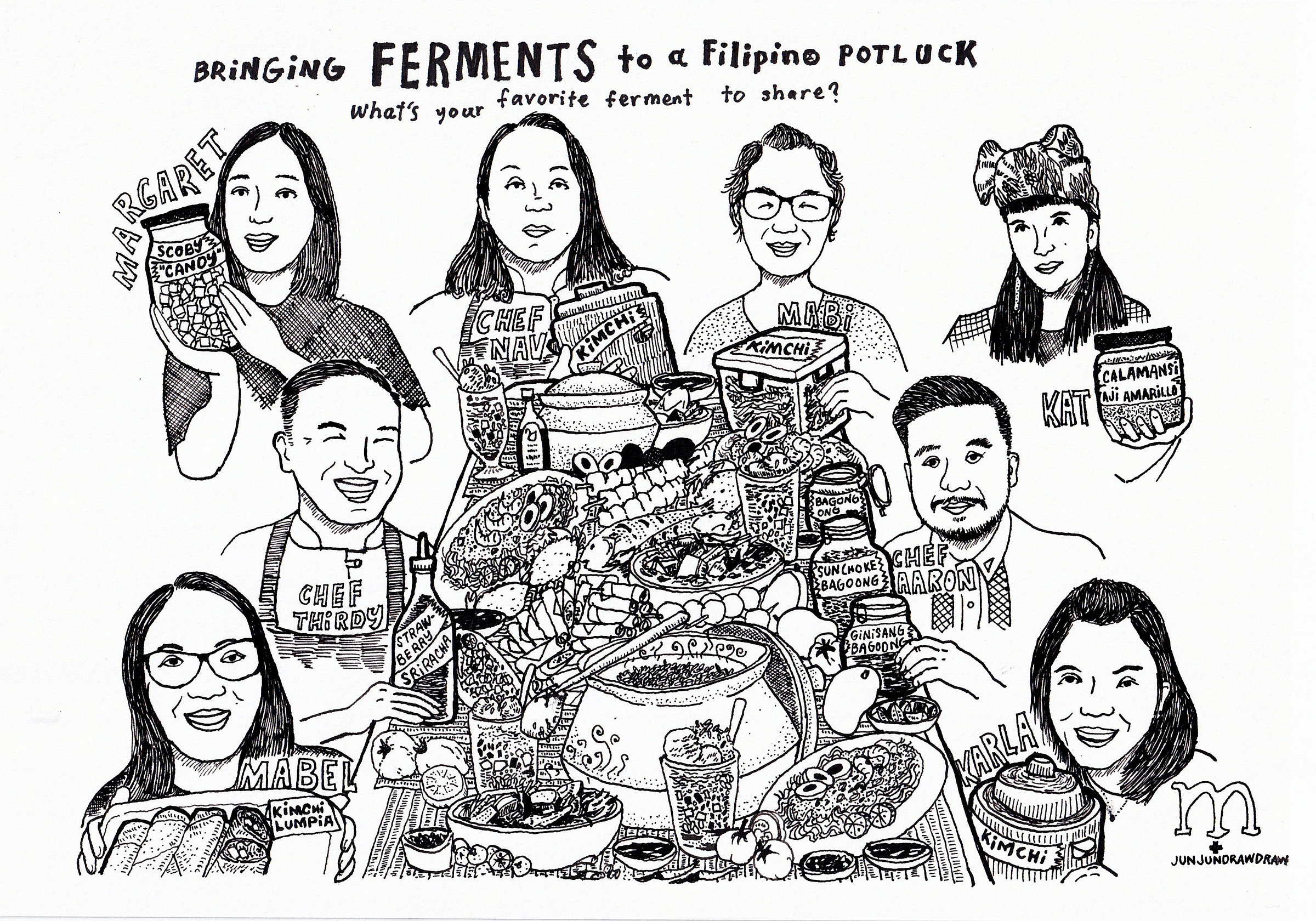

Hello, and welcome to another meryenda Monday. Currently, meryenda is a reader-supported independent publication. If you find value in our work or use it as an educational resource, consider becoming a paid subscriber for $5/mo or $48/year. If you’d rather make a one time donation, please reply to us directly so we can work something out. Your contribution allows us to nurture this space such as commission works from our community. This issue features illustrator Ariel Dungca of JunJunDrawDraw. Maraming salamat 🫶

Our guests for this issue include Hapag and Starter Sisters from Manila, Philippines; Kat Cortez and Margaret Sevenjhazi from unceded Gadigal land also known as Sydney, Australia; and Aaron Verzosa of Archipelago from Seattle, Washington.

Conversations in this feature have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Keeping the Culture(s) Alive

One thing I’ve been thinking about lately as I go through fermentation resources is the exchange of microorganisms. I get it— it’s easy to glance over the process if you’re trying to understand this ecosystem of growth and decay purely through scientific language. Take, for example, toyo (soy sauce) production, which requires the interaction of mold, yeast and bacteria. The traditional process described in Philippine Fermented Foods by Priscilla Chinte-Sanchez is as follows:

“The soybeans are washed, soaked in water overnight with several changes of water to prevent buildup of microorganisms”

“The dried starter culture mold consisting of rice and spores is first mixed with the roasted wheat flour and then added to the cooked soybeans at the rate of 1% by weight…”

“The soybeans covered with mold mycelia are transferred to a fermentation vessel… The starter culture, consisting of Pediococcus halophilus, Saccharomyces rouxi, and Torulopsis versatilis, is added and mixed thoroughly. The addition of lactic acid bacterium and yeast inoculate encourages desirable fermentation…”

What occurs at a microbial level can be hard to appreciate because it is invisible to the human eye. Yet it is this symbiosis, the trillion tiny interactions in this dynamic affair, that transforms the food we consume.

As I investigate the work of microbes, I think about the everyday tiny acts of people. The gestures that can, over a lifetime, leave a lasting impact on our community and the world around us. It might be a bit odd to look at microbes and ask, what can fermentation teach us about the human experience?

I know this leans into a very grand question. Is it even something that can be explored within the context of fermentation? Perhaps it’s best to first prime the pump of this invitation and ask: what draws people to ferment, anyway?

Margaret Sevenjhazi is a cook, food writer and fervent fermenter who runs Bottomfeeder, a consortium of zero-waste recipes. She shares her recipe for homemade adobo pickled mushrooms, a garnish she uses in lugaw, a humble rice porridge. I am reminded of how fermentation can turn everyday ingredients into a delightful rare treat. It can grant a break to the enduring task of meal preparation and be an antidote for repetition.

“Extra self sufficiency is a big thing that comes from being able to ferment and preserve food yourself. You don't necessarily have to make your own vinegar, atchara or your own banana ketchup every week or preserve every vegetable. The beauty of being able to ferment, preserve and pickle is that you can tailor it to your personal situation and needs. You can choose not to rely as much on supermarket products and things made with questionable ingredients and preservatives.”

There’s Mabi David, Mabel David and Karla Rey— who collectively run Starter Sisters, a space that celebrates fermenting in the Philippines. Mabi and Mabel are sisters raised in Pampanga in central Luzon, a province known for its fermented foods. As kids, they ate pindang (fermented carabou meat), burong kanin (fermented rice), and burong hito (fermented rice and catfish mixture). The three rekindled their roots in fermentation for different reasons. For Mabi, fermentation brings back a sense of self-agency:

“[Fermentation] really brought home the fact that food can heal us and we can actually exercise control over our health without having to rely on big pharma. It felt very empowering when I started fermenting and saw some of my issues corrected simply with the help of bacteria. By creating a hospitable environment for good microbes to thrive— that felt liberating to me. And eventually understanding that the microbes in our bodies as well, like in our hands, help create a ferment that's unique. I think in Korea they call it the ‘hand taste.’

Organic food, when they're not pumped with pesticides, also bring with them the bacteria from the soil. That connection, I found very moving— how my body is connected to land and then to all these millions of microorganisms and they're all working together to heal ourselves. I think that's one of the dimensions of fermentation that I found moving and captivating.”

Ferments are carried across generations under the care of hand memory and passed down through vessels inhabited by collaborative microbes waiting to spur the next batch. It’s a practice that relies heavily on the senses: on seeing, smelling, tasting, even feeling. Brines bubble. Dough rises. Saccharine sap morphs into booze before fizzling into vinegar. Grains caramelize into a regal gold merely at the passing hand of time.

Industrialized ferments strip away the sensory, exchanging it instead for valorized consistency and predictability. Yet there are some individuals, like Chef Nav of Hapag, who relishes in the excitement of the sometimes fickle unfolding of fermentation:

“I started off with pickling because it was so easy to understand. Then I moved on to fermenting because I was surprised with what you came up with as time went on. It only gets better through time, although sometimes it goes bad. Some things do go bad or go too sour, but it was just very cool to me that you can produce something that you can't actually use right away.

If you taste a ferment maybe once a week, you'll see how it changes color, flavor, how deep it tastes. And then sometimes you can use it differently as it ages.

Let's say for example, a miso that's a month old. You can use it for a soup. If you age it a bit more, it'll actually be good for sofrito. There's just a lot of things that intrigued me and I just kept going. I honestly feel with the amount of ferments we have here, we're just scratching the surface. What drew me to fermentation was that cool waiting game.”

Ah, patience. A virtue that has atrophied with modern day convenience and same-day shipping. If there’s a common thread I want to emphasize among these conversations, it’s that fermentation is a humbling practice. After all, you’re working with microbes, living things that too adapt with the flux of the environment.

While it’s easy for these conversations to extend beyond the kitchen, there are ways in which fermentation also stretches the realms of cooking. I think about the Philippines and its surrounding ingredients. In the kitchen, freshness is often the pillar for quality. How many times have you you seen ‘freshly flown from Japan’ displayed proudly on a menu? I can’t help but think of what this ultimately leads to outside the lattice of gastronomic pleasures. Huge carbon footprints. Overfishing. Mono-crops.

Fermentation, on the other hand, embraces the given environment and explores inside its boundaries. It’s a practice that somehow multiplies within its parameters, looking at familiar bases to construct endless riffs.

Kat Cortez is a food scientist, fermentation-dabbler and passionate gardener living on unceded Gadigal land or Sydney, Australia. She houses a growing forest of ferments; among her collection is a prized jar of calamansi and aji amarillo kosho. She uses calamansi rinds and aji amarillo pepper to make a variation of yuzu kosho, a Japanese citrus chili paste traditionally made with yuzu and togarashi chili pepper. She holds it proudly, while we discuss the ways in which fermenting weaves value into the fabric of our daily motions.

“Fermentation… I can't fault it. I can't see what's wrong with it. I feel like that's the key to solving basically every world problem in relation to food. It prevents food waste. It makes food taste better. It makes it nutritionally even better than what it was before. It captures the essence of a season. It helps stretch out something that would otherwise not go very far if you didn't ferment it.

To make kimchi or sauerkraut, for example, does not cost a lot. All you need is salt, cabbage, and that's it. So whereas if you were to buy it in a store, it might cost you $20-$30 for a jar when you can make it yourself.

But in that way, you know how much effort it takes and that you've made that yourself. You're connecting with your food more. You're able to connect with your community because you can share it with everyone around you.”

Hapag is a Filipino restaurant located in Quezon City exploring creativity with ferments. Chef Thirdy Dolarte discusses the kitchen’s approach to palabok, a saucy Filipino rice noodle dish:

“The usual palabok, you make a sauce made of aromatics, rice flour, achuete, and you finish it with stock.… usually prawn stock or chicken stock. What we're doing now is adding a depth of flavor using miso that's made out of pumpkin and gamet seaweed.

The process that Nav and I usually do is, he makes the misos and any ferments and I try to utilize it and apply it in Filipino food. I think most Filipinos, they're not aware that they're using ferments like vinegars, patis, bagoong, buros. It's just amazing to see Nav's vision of fermentation and apply it in Filipino food.”

I am not at all diminishing the importance of freshness or seasonality. There are many restaurants sourcing locally (and thoughtfully, because I would argue that locally sourced does not always mean quality) and it’s amazing. What I mean is fermentation can manifest a deeper appreciation for culinary and cultural building blocks, the fading heirloom treasures gifted by our ancestors.

Aaron Verzosa, chef and owner of Archipelago (named 2019 Eater restaurant of the year) in Seattle, Washington sources ingredients easily accessible in the Pacific Northwest such as salmon, sunchoke, Matsutake mushroom, and Oregon pink shrimp to use as bases for his cold-fermented bagoong. He makes these bagong ong (that new new, he says—a nod to his linguistics background) for guests who have allergies or dietary restrictions while emphasizing the region’s surrounding bounty.

“Right now, in the world of fermentation we live in, we're so quick to look at kojis and misos and garums because of the Noma aspect and its effect in the world of fermentation— which is I think awesome. But at the same time, for me, there’s a lot in our bag already. There's a massive runway for just the world of bagoong… I can spend my entire career just building what we already have or trying to understand that. That’s always been our drive— trying to say, ‘How can we expand on that?’”

To Verzosa, fermented foods are necessary in healthy food systems. After all, he continues, ferments not only exude diversity and representation by driving appreciation of nuances in a culture, but also goes back to the necessities of sustainability within a home.

If there’s one takeaway from this entire discussion, it’s that fermentation is for anyone, anywhere. It always has and always will be. Fermenting can exercise food flexibility, which, like the creativity of a chef in the kitchen, is a muscle I believe can be nurtured to nourish. Mabel David of Starter Sisters speaks about how fermentation has changed her relationship with food:

“For me, one of the good things about fermentation is that you can actually limit your food waste. Whenever I'm faced with a vegetable that I really don't know what to do with— because sometimes with a CSA (community-supported agriculture), you have a lot of radishes and a lot of these greens that you're not familiar with— it made me think okay, maybe I can ferment this. It doesn't have to rot in my kitchen crisper. I'm still guilty of that, sometimes, but I think I'm more mindful of the food that I get and what I can do with it.”

The more I immerse myself in ferments, the more I am embracing that humans and microbes aren’t so different. As I wrap up this month of fermentation, I want to bring forward John Paul Lederach, author and practitioner in the fields of conflict transformation and peacebuilding, and his work on what he calls critical yeast. He says this:

Of all the ingredients in bread making, yeast is the smallest. But smallness has nothing to do with the size of potential change. What you look for is the quality of what happens if certain sets of people get mixed…. a few strategically connected people have greater potential for creating social growth than large numbers of people who think alike.

So I return to the question I posed earlier: what can fermentation teach us about the human experience? It is when we knead spaces for conversation that we can find more ways to connect with our food and culture more richly. Like yeast that come together to leaven bibingka and bread, it is a mixture of voices and perspectives, I believe, that kindles the most substantial change.

At the end of our conversations, I asked each guest: What ferment would you bring to a potluck? Here are their answers.

Thirdy Dolarte: Strawberry sriracha or if you have sinigang, I'll bring the patis.

Margaret Sevenjhazi: I think it would be the SCOBY candy because everyone just thinks it's jelly.

Kat Cortez: My calamansi and aji amarillo kosho. Basically you use citrus, chili, and salt and then you just blend it all together and ferment it. I figured out a way to do it with calamansi where it's not bitter as well because I don't know if you've tried working with calamansi rinds, but they're super bitter. But yeah, I am very proud of this.

Mabi David: Burong mustasa (pickled mustard leaves) or kimchi.

Kevin Navoa: Kimchi works well in a pot luck. I don't think if I bring misos to a potluck people will understand what I'm doing. I think that's the safest one I can bring and maybe some shoyu or soy sauce that we made in-house.

Karla Rey: Sauerkraut is the most familiar, but also kimchi.

Mabel David: Kimchi lumpia. It gives the lumpia that acidic and spicy flavor that we usually get when we dip it in pinakurat (spiced vinegar) but now you have it there in your lumpia.

Aaron Verzosa: I'd bring bagoong, but it'd be a pallet of bagoongs— one for the folks who are allergic to shellfish, one for the vegetarians, the vegans, people who don’t like mushrooms. And then have of course, whatever pulutan to drop into there.

A special salamat to these spectacular individuals

Guests

Aaron Verzosa of Archipelago: https://www.instagram.com/archipelago_pnw

Kat Cortez: https://www.instagram.com/katgot.hertongue

Mabi David, Mabel David + Karla Rey of Starter Sisters: https://www.instagram.com/startersistersph

Margaret Sevenjhazi: https://www.instagram.com/bottomfeeder.food/

Nav + Thirdy Dolarte of Hapag: https://www.instagram.com/hapag.mnl/

Illustration

Ariel Dungca (or as his Filipino family calls him, Jun-Jun) is an artist, trained landscape architect, and educator. He currently calls beautiful Honolulu, Hawai’i home. Jun spent the first part of his childhood on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. His family immigrated to the United States, where he spent the second half of his childhood in New England. He found love in Boston and followed her to the Bay Area in California. Today he resides with his wife [Phoebe!] in the “Gathering Place” of the Hawaiian Islands [O’ahu!]. These people and places inspire Jun’s stories. You can find his work here.

In case you missed it 👀

Fizz, Funk, and Flavor: Following Philippine Ferments

That’s not to say the practice of fermentation is fraught. This generation, fueled by curiosity and growing food conscientiousness, is revitalizing this seemingly mystified practice. Fermentation has never been more exciting and in a time that urges humankind to rekindle care and sensibility for the world around them, fermentation has never been more relevant.

The Last Vestiges of Philippine Sea Salt

One day, Philippine salt can silently fade into another cultural artifact. We’ve lived without Philippine salt all this time so why care now when finely ground salt is conveniently within our reach?

Where Does Ube Really Come From?

As a generation accustomed to store-bought ube jam, we’ve unknowingly detached ourselves from ube’s genetic diversity; canisters and packages have erased local cultivar names such as kabus-ok, tamisan, binanag, and sapiro from conversation. Even color variations— ranging from marbled white-purple to deep violet— are eclipsed by a defining alluring purple that paints every ube reincarnation.

Always so good! Thank you for this!